Building upon many years of privately shared thoughts on the real benefits of Stoic Philosophy, Liam Milburn eventually published a selection of Stoic passages that had helped him to live well. They were accompanied by some of his own personal reflections. This blog hopes to continue his mission of encouraging the wisdom of Stoicism in the exercise of everyday life. All the reflections are taken from his notes, from late 1992 to early 2017.

The Death of Marcus Aurelius

Thursday, April 30, 2020

Tidbits from Montaigne 8

I want death to find me planting my cabbages.

—Michel de Montaigne, Essays 1.20

Seneca, On Peace of Mind 9.5

Let

a man, then, obtain as many books as he wants, but none for show.

"It

is more respectable," say you, "to spend one's money on such books

than on vases of Corinthian brass and paintings."

Not

so: everything that is carried to excess is wrong. What excuses can you find

for a man who is eager to buy bookcases of ivory and citrus wood, to collect

the works of unknown or discredited authors, and who sits yawning amid so many

thousands of books, whose backs and titles please him more than any other part

of them?

As I grow

older, I become ever more conscious of the confusion between appearance and

reality. As we place greater value on externals over internals, we also focus

our attention on the impressions of things instead of the nature of things. We

settle only for how it feels, failing to look through at what it is. Passion ceases

to be tempered by reason.

It saddens

me when I see the disconnect in others, and it shames me when I see it within

myself. The temptation runs deep, if for no other reason than how the inaction

of conformity seems so much more comfortable than the action of reflection.

I detect

even the odd contradiction of following a certain image that vainly insists

upon following no image at all, of buying and selling masks of manufactured individuality,

of caring that others take notice of how we pretend not to care what they think

of us.

It would

be easy to blame a love of wealth for all this, but I suspect it goes far deeper

than just giving everything a dollar value. Money can itself be yet another

convenient veneer to cover up any natural worth. No, I wonder if the root cause

is a fear of genuinely being ourselves, sheepishly expressed in becoming whatever

we believe the fashion of the hour tells us we must be.

Such

posing and posturing can be found in all aspects of life, even as I have personally

experienced it most closely in the field of education. Some people promote

their images through the lure of sex, and others through the intoxication of

power, and yet others through the illusion of insight. For those who are

impressed by the trappings of culture and refinement, clever phrases can be as

seductive as pouty lips.

If I wish

to only appear as thoughtful and profound, books can become the perfect accessory.

I need not read them, of course, only display them, and I have then presented a

package of how I would like to be perceived. It can be as simple as having a collection

of poems casually peeking out of my bag, or as grand as filling an entire room

with trophies of intellectual status.

The next

time I open a book, let me be certain I am not intent on being admired. The

next time I add a volume to my library, let my concern be for how understanding

its contents might improve my soul, not for how showing it off will increase my

reputation.

Written in 10/2011

Wednesday, April 29, 2020

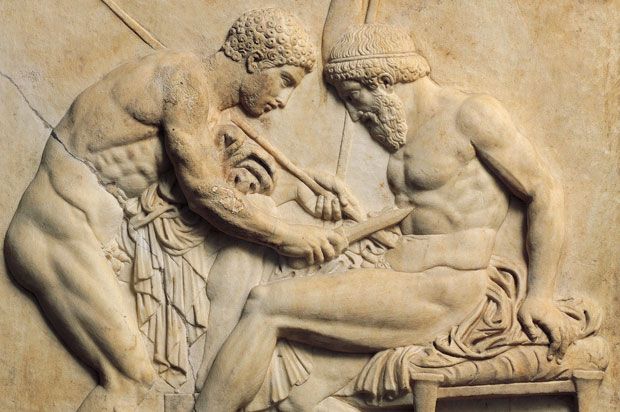

Diogenes and Alexander

Here are a few different images of the legendary meeting between Alexander the Great and Diogenes of Sinope.

The stories about their conversation may well be apocryphal, but they are nevertheless quite telling.

It is said Diogenes was relaxing one fine day, and Alexander approached him imperiously, asking, "What can Alexander do for Diogenes?"

"Stay out of my sunlight!" came the reply.

Perhaps Alexander was feeling especially noble that day, so instead of becoming angry at such impudence, he took it kindly. "If I was not Alexander, I would wish to be Diogenes!"

"And if I was not Diogenes," said the philosopher, "then I would still wish to be Diogenes!"

Another version has Alexander finding Diogenes picking through a pile of bones.

"What are you doing, Diogenes?"

"I am searching for the bones of your father, but I cannot seem to tell them apart from the bones of a slave."

Thomas Christian Wink (1782)

Bartholomeus Breenbergh (early 1600's)

Jacques Gamelin (1763)

Gaspar de Crayer (c. 1630)

School of Giovanni Francesco Romanelli (early 1600's)

Gaetano Gandolfi (1792)

Jan Thomas (1672)

Jean-Baptiste Regnault (1776)

Matvei Ivanovich Puchinov (1762)

Nicolas-Andre Monsiau (1818)

Pierre Paul Sevin (c. 1700)

Ivan Tupylev (1787)

Giovan Battista Langetti (c.1650)

Sebastiano Ricci (c. 1700)

Monday, April 27, 2020

Dhammapada 78

Do not have evil-doers for friends, do not have low people for friends.

Have virtuous people for friends, have for friends the best of men.

Musonius Rufus, Lectures 9.10

But tell me, my friend, when Diogenes

was in exile at Athens, or when he was sold by pirates and came to Corinth, did

anyone, Athenian or Corinthian, ever exhibit greater freedom of speech than he?

And again, were any of his contemporaries freer than Diogenes? Why, even

Xeniades, who bought him, he ruled as a master rules a slave.

But why should I employ examples

of long ago? Are you not aware that I am an exile? Well, then, have I been

deprived of freedom of speech? Have I been bereft of the privilege of saying

what I think? Have you or anyone else ever seen me cringing before anyone just

because I am an exile, or thinking that my lot is worse now than formerly?

No, I'll wager that you would say

that you have never seen me complaining or disheartened because of my

banishment, for if I have been deprived of my country, I have not been deprived

of my ability to endure exile.

I am always pleased to see Diogenes offered as an

example, because I have a special attachment to his unconventional manner of

thinking and living, much to the frustration of those who know me. I heartily nod

in agreement when Musonius repeatedly refers to Diogenes in this lecture, knowing

how powerful an inspiration that bewildering man can be, having made so much of

himself out of so little, and willing to see every obstacle as an opportunity.

But why only look to the lives of strangers from

the past, when we can also look to our own situations, right here and now, to

strengthen our commitments? Musonius finally reminds us that he is also an

exile, and that this has hindered him no more than it did Diogenes.

I am not certain exactly when the Lectures were originally presented or written down, but

Musonius, following in the footsteps of Diogenes, was exiled twice from Rome, once

under Nero, and then later under Vespasian. I suppose the best philosophers,

those who truly embrace the task, have a knack for making themselves quite unwelcome

by those who wish to maintain their power.

Our own personal experiences might not be as

dramatic as those of Diogenes, or even of Musonius, yet they can still support

exactly the same lessons in life. Most anyone will know something of how it

feels to be left out, to be cast aside, to be considered unworthy of attention.

I have never been kicked out of a city or a

country, not for want of trying, though I have been fired from a job for

speaking my mind, and I have found myself socially shunned by all the members

of a local church for bringing up things that were considered unmentionable.

Though the scale was obviously not as grand, it still taught me that who I am

is not determined by where I am, and that character is not measured by

circumstance.

There was never any formal proclamation to it, and

only my immediate family know anything of how it all happened, but there also

came a moment when I realized I could never go back to my old neighborhood

without causing myself terrible harm. It has been one of the most unpleasant

events of my life, and at the same time one of the most formative events of my

life. There is nothing like losing the familiar and beloved to help you cling

all the more tightly to what is truly your own.

I once got to know a fellow, a fiery and

impassioned journalist, who was forced to flee his home country with his family

in the middle of the night, and then spent the next two decades in the United

States.

He would occasionally have me over for tea, and

though he had a flair for the melodramatic, I couldn’t help but be moved when

he would point to his head and his heart, slowly saying, “Home is here . . . and here.”

He never returned, even after the government that

had harassed him was overthrown, because he insisted that “changing the color

of the flags doesn’t change the nature of the tyrants.” I like to imagine him,

Diogenes, and Musonius now having a good laugh together.

Barely a day passes when I am not also deeply

impressed by some of the people I meet in the most unassuming of situations,

who had to leave their homes on account of poverty or oppression, and who will

still find a way to live in peace and joy. I am not so much interested in the angry

politics of it, as I am in the genuine humanity of it. I see myself complaining

about the pettiest of things, and they show me what a spoiled brat I can be.

Exile, deprivation, and hardship are unable to stop

me from understanding and loving, and so they are unable to stop me from living

well.

Written in 12/2016

Sunday, April 26, 2020

Epictetus, Golden Sayings 120

Does a Philosopher apply to people to come and hear him? Does he not rather, of his own nature, attract those that will be benefited by him—like the sun that warms, the food that sustains them?

What Physician applies to men to come and be healed? (Though indeed I hear that the Physicians at Rome do nowadays apply for patients—in my time they were applied to.)

"I apply to you to come and hear that you are in an evil case; that what deserves your attention most is the last thing to gain it; that you know not good from evil, and are in short a hapless wretch."

A fine way to apply! Though unless the words of the Philosopher affect you thus, speaker and speech are alike dead.

Saturday, April 25, 2020

Aesop's Fables 20

The Fox and the Mask

A Fox had by some means got into the store-room of a theater. Suddenly he observed a face glaring down on him, and began to be very frightened; but looking more closely he found it was only a Mask, such as actors use to put over their face.

"Ah," said the Fox, "you look very fine; it is a pity you have not got any brains."

Outside show is a poor substitute for inner worth.

Seneca, On Peace of Mind 9.4

What

is the use of possessing numberless books and libraries, whose titles their

owner can hardly read through in a lifetime? A student is overwhelmed by such a

mass, not instructed, and it is much better to devote yourself to a few writers

than to skim through many.

Forty

thousand books were burned at Alexandria: some would have praised this library

as a most noble memorial of royal wealth, like Titus Livius, who says that it

was "a splendid result of the taste and attentive care of the kings."

It

had nothing to do with taste or care, but was a piece of learned luxury, no,

not even learned, since they amassed it, not for the sake of learning, but to

make a show, like many men who know less about letters than a slave is expected

to know, and who uses his books not to help him in his studies but to ornament

his dining room.

Many people

are under the impression that the academic world is a profound and lofty place,

inspired by the noble love of truth and a selfless commitment to service. This

is sadly not the case. You will indeed find some truly decent folks in what

they call higher learning, just as you will also find decent folks most

anywhere else, but in the end, it is shamefully reduced to a business like all

the others.

The

driving force is still profit, and while it isn’t merely a matter of getting rich,

there is much squabbling, scheming, and backstabbing going on in order to win

the greatest status and fame. In this sense, “scholars” must become masters of promoting

an image if they wish to survive in their field.

What

matters most is not what you know, but having the confidence and the cleverness

to give the appearance that you know. One forges alliances of convenience in order

to be considered an authority and pays out favors in order to be revered as an

expert. The most effective tool is ultimately to denigrate others, politely and

dryly in public, viciously and passionately in private. Through it all, a

refined smugness is an absolute requirement.

They really

don’t like it when you point this out, just like politicians get deeply offended

when you question their honesty.

I can

only blame myself for having fallen for this, lock, stock, and barrel. I was

especially taken with the idea of being “well read”, of presenting the illusion

that I was fluent in all the most important works of philosophy and literature,

hoping that I could drop the most insightful quotes and relevant references with

barely an effort.

I still

cringe when I think of that ever-growing list I had throughout high school and

college, of all the books I was sure others expected me to be familiar with. I

was convinced I had it made when my peers looked on in envy, while my

professors pretended to be impressed. What a waste, what a foolish game, what a

pack of lies. The issue was never about learning at all, but about making a

show of learning, of turning it into a circus act.

As with

all things shallow and vain, there was a great love of breadth at the expense

of depth, of believing that more was better. I read very little, but glanced

over very much, such that I saw it as a weakness instead of a strength to admit

that I didn’t know something. Piles and piles of books, strategically strewn across

shelves and desks, became like substitutes for actual understanding.

My alma

mater would brag about the scope of their library, while still being quite jealous

that the Ivy League school down the street had four times as many volumes. One fiery

professor, who was never afraid to speak his mind, and so never received tenure,

described it quite well: “What does it matter how many books we have? When was

the last time you saw any of our students actually reading them, except to

extract a reference for a bibliography?”

I learned

the hard way that if I even felt the need to tell people that I had read it, I probably

hadn’t read it at all, or at least not for any of the right reasons.

I have no

doubt that many great books were lost when the library at Alexandria fell into

ruin; I have often dreamed about reading some of those texts that never

survived into the modern era, like Aristotle’s dialogues, or the writings of the

early Stoics and Cynics, and I wonder if they might still be here if history

had unfolded just a little bit differently.

Yet

Seneca is quite right. It was never the gathering together of books, at any

time or in any place, that made anyone decent. A commitment needs to be made,

one soul at a time, to the act of living well, with eyes wide open.

I once

met a fellow, with virtually no formal schooling, who had built a system of life

values around a worn and tattered copy of the Handbook

by Epictetus, given to him by his mother. He knew nothing about who wrote it,

or when it was written, or why it mattered in the grand scale of intellectual

history.

When I

spoke to him of Stoicism, or of other authors, he simply shrugged. All he knew

was that his mother read it, and because he loved her, he read it too. There

was a man who was far better than I could ever be.

The world

doesn’t become a better place because we stockpile knowledge; the world becomes

a better place when individual people choose to live with wisdom, however

humble its scale. A single book read with love is far more important than many

books displayed out of pride.

Written in 10/2011

Friday, April 24, 2020

Thomas a Kempis, The Imitation of Christ 3.12

Of the inward growth of patience, and of the struggle against

evil desires

1. O Lord God, I see that patience is very necessary unto me; for many things in this life fall out contrary. For howsoever I may have contrived for my peace, my life cannot go on without strife and trouble.

1. O Lord God, I see that patience is very necessary unto me; for many things in this life fall out contrary. For howsoever I may have contrived for my peace, my life cannot go on without strife and trouble.

2. "You speak truly, My Son. For I will not that you seek

such a peace as is without trials, and know no adversities;

but rather that you should judge yourself to have found peace,

when you are tried with manifold tribulations, and proved by

many adversities. If you shall say that you are not able to

bear much, how then will you sustain the fire hereafter? Of two

evils we should always choose the less. Therefore, that you

may escape eternal torments hereafter, strive on God's behalf

to endure present evils bravely. Think you that the children

of this world suffer nothing, or but little? You will not find

it so, even though you find out the most prosperous.

3. "'But,' you will say, 'they have many delights, and they

follow their own wills, and thus they bear lightly their

tribulations.'

4. "Be it so, grant that they have what they list; but how long,

think you, will it last? Behold, like the smoke those who are

rich in this world will pass away, and no record shall remain of

their past joys. Yes, even while they yet live, they rest not

without bitterness and weariness and fear. For from the very

same thing wherein they find delight, thence they oftentimes have

the punishment of sorrow. Justly it befalls them, that because

out of measure they seek out and pursue pleasures, they enjoy

them not without confusion and bitterness. Oh how short, how

false, how inordinate and wicked are all these pleasures! Yet

because of their sottishness and blindness men do not understand;

but like brute beasts, for the sake of a little pleasure of this

corruptible life, they incur death of the soul.You therefore,

my son, go not after your lusts, but refrain yourself from your

appetites. Delight you in the Lord, and He shall give you your heart's desire.

5. "For if you will truly find delight, and be abundantly

comforted of Me, behold in the contempt of all worldly things and

in the avoidance of all worthless pleasures shall be your

blessing, and fullness of consolation shall be given you. And

the more you withdraw yourself from all solace of creatures,

the more sweet and powerful consolations shall you find. But at

the first you shall not attain to them, without some sorrow and

hard striving. Long-accustomed habit will oppose, but it shall

be overcome by better habit. The flesh will murmur again and

again, but will be restrained by fervor of spirit. The old

serpent will urge and embitter you, but will be put to flight by

prayer; moreover, by useful labor his entrance will be greatly

obstructed."

Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy 4.31

“But

you will ask, ‘What more unjust confusion could exist than that good men should

sometimes enjoy prosperity, sometimes suffer adversity, and that the bad too should

sometimes receive what they desire, sometimes what they hate?’

“Are

then men possessed of such infallible minds that they, whom they consider

honest or dishonest, must necessarily be what they are held to be? No, in these

matters human judgment is at variance with itself, and those who are held by

some to be worthy of reward, are by others held worthy of punishment.

“But

let us grant that a man could discern between good and bad characters. Can he

therefore know the inmost feelings of the soul, as a doctor can learn a body's

temperature? For it is no less a wonder to the ignorant why sweet things suit

one sound body, while bitter things suit another; or why some sick people are aided

by gentle draughts, others by sharp and bitter ones.

“But

a doctor does not wonder at such things, for he knows the ways and

constitutions of health and sickness. And what is the health of the soul but

virtue? and what the sickness, but vice? And who is the preserver of the good

and banisher of the evil, who but God, the guardian and healer of minds?”

—from

Book 4, Prose 6

I become

far too hasty in my judgment, too narrow in my scope, when I am ever so quick

to determine who should be rewarded and who should be punished. I first commit

the error of making foolish assumptions about what is right and wrong to begin

with, and I then compound it by thinking I fully apprehend the hearts and minds

of others, that I can see all their most hidden intentions, and grasp all the

circumstances they have had to face.

Who am I

to flippantly decide such things? Let me spend some of that time and energy

attending to myself, and slowly learning something more about the deeper

workings of Providence.

We are

easily tempted to give legal, or financial, or medical advice, even if we know

next to nothing about such matters. I sometimes observe that it is precisely

those who understand the least who will often dictate to us the most. I would

be best served by trusting competent and experienced lawyers, bankers, and

doctors over the loud fellow at the end of the bar.

Should

it be any different when it comes to questions of morality and justice? Pay

heed to the lover of wisdom, who has humbly and carefully learned a little something

of his own nature, and the order within all of Nature. He will advise patience

and compassion, an open mind and an open heart.

A fine

doctor will comprehend the nature of the disease, as well as the nature of the cure;

he sees what is wrong, and then how to make it right. Even when I can’t figure

out all the difficult terms or the mysterious causes he speaks of, I will trust

that he can make me well. How odd that I will gladly follow his directions to

heal my body, but I stubbornly refuse to follow God’s directions to heal my

soul.

I ought

to step back. Have I truly made sense of what is good or bad for a human being,

right to the very core? Am I too easily impressed by the appearance instead of

the content? Perhaps what is worthy of praise or blame is very different than I

at first think, and my estimation of character is founded on a crafty illusion.

Why am I

assuming that receiving riches, or gratification, or fame is necessarily of

benefit, while receiving poverty, or hardship, or anonymity is necessarily of

harm? Perhaps what I consider rewards or punishments are not that at all, but

serve to assist our moral health in ways I have not foreseen.

Too

often I am concerned with the accidents over the substance, and so my very

measure of losses and gains is disordered. I worry about property, and

luxuries, and reputation, when I should be focused on the pursuit of virtue and

the avoidance of vice. Integrity is worth more than anything in my bank account,

and love commands a far greater value than all the worldly vanities put

together.

Once I

begin to see the human good from the perspective of character, I will also

begin to see that Providence prescribes prudent remedies. As long as it can encourage

me to improve the excellence of my soul, it works with justice. The Doctor knows

best.

Written in 11/2015

Thursday, April 23, 2020

Wednesday, April 22, 2020

Musonius Rufus, Lectures 9.9

But, you insist, Euripides says

that exiles lose their personal liberty when they are deprived of their freedom

of speech. For he represents Jocasta asking Polynices her son what misfortunes

an exile has to bear. He answers,

"One greatest of all, that

he has not freedom of speech."

She replies,

"You name the plight of a

slave, not to be able to say what one thinks."

But I should say in rejoinder:

"You are right, Euripides, when you say that it is the condition of a

slave not to say what one thinks when one ought to speak, for it is not always,

nor everywhere, nor before everyone that we should say what we think.

“But that one point, it seems to

me, is not well-taken, that exiles do not have freedom of speech, if to you

freedom of speech means not suppressing whatever one chances to think. For it

is not as exiles that men fear to say what they think, but as men afraid lest

from speaking pain or death or punishment or some such other thing shall befall

them. Fear is the cause of this, not exile.

“For to many people, no to most,

even though dwelling safely in their native city, fear of what seem to them

dire consequences of free speech is present.

“However, the courageous man, in

exile no less than at home, is dauntless in the face of all such fears; for

that reason, also, he has the courage to say what he thinks equally at home or

in exile."

Such are the things one might

reply to Euripides.

We understandably become frustrated when we are

denied the things we feel we deserve, such as a fair wage, or the security of a

home, or the recognition of our peers. Nature may have rightly intended them

for us, but there are still those who would forcibly keep them from us, and

this is never an easy obstacle to face.

I remind myself that while I cannot always determine

what is done to me, I can always determine what I will do. If another acts

unjustly, it is then my place to respond justly, whatever the external conditions

might be, I still retain the freedom of my own judgment.

A practical rule I keep for myself is that I should

indeed fight to be treated fairly, except where my demands would force me to compromise

my own virtue, or discourage the exercise of virtue in others. It may sound too

simple, but it has saved me from quite a few pointless conflicts, by placing

the superior and the inferior in a proper context.

Nevertheless, I will still struggle with

limitations placed on my freedom of expression. It is one thing to steal my property,

but quite another to muzzle my voice. As a result, I can easily grow angry, and

become quite indignant, and be tempted to stomp about in protest.

Here is one way where alien forces seem to intrude

on something deeply personal, and at first it feels as if it crosses that

boundary between the outside and the inside of me. It makes me quite anxious,

in an almost claustrophobic sense. “Stand back!” I wish to say. “You’ve gone

too far this time!”

Exile, of any sort, will be like so many other changes

of circumstance, where I must learn a whole new set of customs and rules, where

a behavior I am accustomed to is suddenly considered quite unacceptable, where censorship

can be a harsh irritant. But let me ask myself honestly if anything has really

been lost, and if the limitation on my freedoms is ultimately of my own making,

not made by others at all.

“But they won’t let me speak my mind or say what I

truly think! I’ve been put in a place where I can’t be myself!”

Let me be very careful. Have I been denied the

power to think as I would choose to think? Not in any way; no one has reached

into my head to change my judgments. Have I been denied the power to speak as I

would I choose to speak, or to act as I would choose to act? Again, let me be very

careful. Are all of the modes of my communication and expression closed off to

me?

Back in grammar school, during one of those regular

moments where a set of bullies enjoyed throwing their weight around, I was held

down by two fellows, while a third covered my mouth with his hand so that I

wouldn’t yell out. I was then slowly told by the fourth that I would be

required to literally kiss his bare ass, or I would be “hurt like I’d never

hurt before!”

In hindsight, such a demand tells me quite a bit

about such people. I later came across many variations over the years, more

refined in form but identical in content.

What could I do? I winked at him, twisting my face

in the most exaggerated and ridiculous way I could manage. He didn’t like this

at all, and slapped me across the face a few times. They finally grew tired of

their plan, departing on their way after planting a few kicks.

Sometimes the smallest gesture, the slightest

glance, the tiniest expression can take on the greatest significance. That is

still freedom.

Why will I not act as I should? Barring incapacitation

or death, it is only my own fear that stands in the way. As overwhelming as it

may seem, I can master my fear, just as I can master my anger or my lust, with

patient and caring attention. It may not happen overnight, but it can happen with

conviction and fortitude.

Exile has never done me any wrong. Neither being at

home nor being abroad will change the fact that my choices are only as good as

my priorities. How much does it hurt? Does it hurt enough to violate my values?

My values are only as good as they are important to me.

Written in 12/2016

IMAGE: Euripedes

Tuesday, April 21, 2020

Stoic Snippets 22

The ruling power within, when it is in its natural state, is so related to outer circumstances that it easily changes to accord with what can be done and what is given it to do.

—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 4.1

Monday, April 20, 2020

Seneca, On Peace of Mind 9.3

Let

us then teach ourselves to be able to dine without all Rome to look on, to be

the slaves of fewer slaves, to get clothes that fulfill their original purpose,

and to live in a smaller house.

The

inner curve is the one to take, not only in running races and in the contests

of the circus, but also in the race of life; even literary pursuits, the most

becoming thing for a gentleman to spend money upon, are only justifiable as

long as they are kept within bounds.

To take

the most direct path, to make do with just what is needed, to be bound by very

little, and to be content with Nature alone will be the surest aids in living

the happiest life possible.

It is not

necessary to complicate, to ornament and accessorize, to carry the weight of luxuries,

or to seek to be seen and admired. We think we become stronger by tying

ourselves to external diversions, only to find that they are dragging us along

after them.

Someone

once told me that my interest in Stoicism rested on the false premise that the

circumstances of my life were largely outside of my control. He prodded me to

expand the scope of my outside influence, not merely to settle for being

myself. I was willing to listen, because surely a man dies inside when he is no

longer open to learning something new.

“Look, it

isn’t that you can’t have all those things, it’s just that you haven’t figured

out how to go about getting them. You need to be smarter in working your way up

the ladder, you need to suck up a little more over here, and impose your will more

over there. Stop being so damned principled, and be more flexible, otherwise

you won’t get what you want!”

For a time,

those words made me feel rather confused. Perhaps I was just too weak, or not

clever enough, or unwilling to look the other way? It took me a while to get my

priorities back in order. This wasn’t a question of being strong enough to get what I wanted; it was a question of being wise

enough to know what I wanted.

Let me, for

the moment, assume that I could have the power to shape the world according to

my own will. This would require, of course, the most remarkable concurrence of

events, but even given such a possibility, is that something I should pursue?

Make me ever

so mighty, far-seeing, and charming! Would it make any difference in what constitutes

a good life?

None of

the other possessions will matter, if I did not first possess myself, and once

I possess myself, I will in turn require very little else in any event. The

temptation to becoming a manipulator comes only from having nothing of one’s

own to begin with. What else do I have if I don’t have the principles of my

conscience?

I was

glad to respect this fellow’s right to think and live as he chose, and I meant

him no ill will, but it threw me for a loop that he wasn’t a banker, or a lawyer,

or an investor, but rather a college professor. Here was an academic, a man who

was supposed to value wisdom above all else, and yet he spoke of compromising

his soul for worldly profit.

It is

interesting that Seneca will now finish this chapter with a consideration of the

vanity, ostentation, and greed of certain types of “scholars”. The lust for

acquisition is hardly limited to a desire for money.

Written in 10/2011

Sunday, April 19, 2020

Wisdom from the Bhagavad Gita 13

The Blessed Lord said:

1. I told this imperishable Yoga to Vivasvat; Vivasvat told it to Manu; and Manu told it to Ikshvâku.

2. Thus handed down in regular succession, the royal sages knew it. This Yoga, by long lapse of time, declined in this world, O burner of foes.

3. I have this day told you that same ancient Yoga, for you are My devotee, and My friend, and this secret is profound indeed.

Arjuna said:

4. Later was Your birth, and that of Vivasvat prior; how then should I understand that You told this in the beginning?

The Blessed Lord said:

5. Many are the births that have been passed by Me and you, O Arjuna. I know them all, while you know not, O scorcher of foes.

6. Though I am unborn, of changeless nature and Lord of beings, yet subjugating My Prakriti, I come into being by My own Mâyâ (Appearance).

7. Whenever, O descendant of Bharata, there is decline of Dharma, and rise of Adharma, then I body Myself forth.

8. For the protection of the good, for the destruction of the wicked, and for the establishment of Dharma, I come into being in every age.

9. He who thus knows, in true light, My divine birth and action, leaving the body, is not born again: he attains to Me, O Arjuna.

10. Freed from attachment, fear, and anger, absorbed in Me, taking refuge in Me, purified by the fire of Knowledge, many have attained My Being.

—Bhagavad Gita, 4:1-10

IMAGE: The Dashavatara, the ten avatars of Vishnu

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)