Building upon many years of privately shared thoughts on the real benefits of Stoic Philosophy, Liam Milburn eventually published a selection of Stoic passages that had helped him to live well. They were accompanied by some of his own personal reflections. This blog hopes to continue his mission of encouraging the wisdom of Stoicism in the exercise of everyday life. All the reflections are taken from his notes, from late 1992 to early 2017.

The Death of Marcus Aurelius

Saturday, December 31, 2022

Friday, December 30, 2022

Sayings of Ramakrishna 192

Wisdom from the Bhagavad Gita 55

1. Fearlessness, purity of heart, steadfastness in knowledge and Yoga; almsgiving, control of the senses, Yajna, reading of the Shâstras, austerity, uprightness;

Seneca, Moral Letters 40.7

And our compatriot Cicero, with whom Roman oratory sprang into prominence, was also a slow pacer. The Roman language is more inclined to take stock of itself, to weigh, and to offer something worth weighing.

Fabianus, a man noteworthy because of his life, his knowledge, and, less important than either of these, his eloquence also, used to discuss a subject with dispatch rather than with haste; hence you might call it ease rather than speed.

I approve this quality in the wise man; but I do not demand it; only let his speech proceed unhampered, though I prefer that it should be deliberately uttered rather than spouted.

—from Seneca, Moral Letters 40

For myself, I have chosen to focus on the contrast between dispatch and haste, between ease and speed, between deliberation and spouting. As is usually the case, Seneca’s words are far mor fitting than any I can come up with on my own. There is no shame in this, as long as I understand something of what he means, and I pass it along it with all the integrity I can muster.

Observe how often we are carried along by our words, instead of being firmly in command of our words; one man is precariously perched on a horse that goes where it pleases, while the other has a skilled hand on the reins. Where I am not guided by a clear sense of meaning and purpose, my speech will run away with me, and I might not be so happy about where I then end up.

However refined the vocabulary, or sweet the tones, or hypnotic the rhythm, it will come to nothing without the inspiration of wisdom. We forget this far too often, when we assume we can pull a fast one by merely going through the motions. I inevitably find myself in trouble after careless words, but I have never had reason to regret a single utterance when I took the time to think it over.

—Reflection written in 1/2013

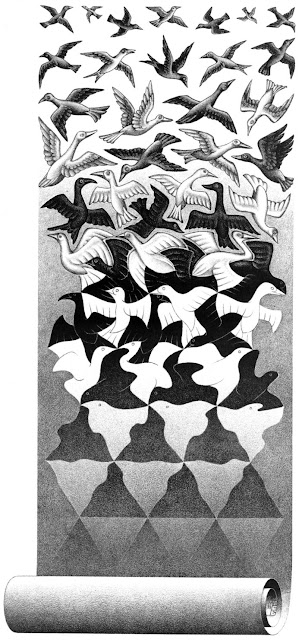

IMAGE: Victor Adam, The Runaway Horse (c. 1850)

Thursday, December 29, 2022

Stoic Snippets 180

Wednesday, December 28, 2022

Wisdom from the Early Cynics, Diogenes 15

Wisdom from the Early Stoics, Zeno of Citium 55

Tuesday, December 27, 2022

Dhammapada 283, 284

So long as the love of man towards women, even the smallest, is not destroyed, so long is his mind in bondage, as the calf that drinks milk is to its mother.

Seneca, Moral Letters 40.6

When Asellius was asked how Vinicius spoke, he replied: "Gradually"! (It was a remark of Geminus Varius, by the way: "I don't see how you can call that man 'eloquent'; why, he can't get out three words together.")

Why, then, should you not choose to speak as Vinicius does?

Though of course some wag may cross your path, like the person who said, when Vinicius was dragging out his words one by one, as if he were dictating and not speaking. "Say, haven't you anything to say?"

And yet that were the better choice, for the rapidity of Quintus Haterius, the most famous orator of his age, is, in my opinion, to be avoided by a man of sense. Haterius never hesitated, never paused; he made only one start, and only one stop.

We are so enamored of the fast talkers with their slippery words that we even think it reflects poorly on a man’s worth if he speaks in a restrained or gradual manner. Is he lazy? Perhaps he’s not quite right in the head?

Yet it would be better for me to stutter like a Publius Vinicius than to be so caught up in bitterness and reproach. If I truly wish to see into the merits of a fellow’s soul, I should pay attention to the quality of what he says, not the pace at which he says it.

I spent several years in grade school with a boy who struggled with stuttering, and I noticed not only how quickly people grew frustrated with his condition, as if he were deliberately doing something wrong, but also how easily he became a target of the cruelest sort of mockery.

Anyone who insists that children are so innocent clearly does not remember the packs of bullies roaming about, compensating for their own insufficiencies by picking on those who were somehow different. I am still deeply ashamed by not standing up for him, and yet he never seemed to blame me after the predators had moved on to fresh victims.

If I only practiced a little patience in listening to him, he had some of the most thoughtful and kind things to say. I’m afraid I don’t know what became of him, though I unfortunately still know far too much about the whereabouts of the ruffians—as adults they continue to draw attention to themselves.

I can only wish that fine boy well, and while I hope he has managed with his condition, I also hope he never lost his constancy.

It hadn’t changed much by college, when, in turn, a young lady with a lisp became an object of derision for the trendy crowd. As she was also hard of hearing, they would ridicule her quite openly, always demeaning her ideas by imitating her pronunciation.

You should not be surprised to learn how these are now among the same folks who claim to be champions of equity and inclusion in the worlds of business and academia. No, they haven’t changed—they are just as glib as they always were.

If push comes to shove, choose to be a Publius Vinicius instead of a Quintus Haterius. Your conscience will thank you.

Monday, December 26, 2022

Seneca, Moral Letters 40.5

Of course she should; but dignity of character should be preserved, and this is stripped away by such violent and excessive force. Let philosophy possess great forces, but kept well under control; let her stream flow unceasingly, but never become a torrent.

And I should hardly allow even to an orator a rapidity of speech like this, which cannot be called back, which goes lawlessly ahead; for how could it be followed by jurors, who are often inexperienced and untrained?

Even when the orator is carried away by his desire to show off his powers, or by uncontrollable emotion, even then he should not quicken his pace and heap up words to an extent greater than the ear can endure.

Yes, I do sometimes find it difficult to distinguish between elegant language and blubbery language; as swiftly as I claim to detect it in others, I am often hesitant to admit it in myself.

The intention clearly plays a role, whether I wish to educate or manipulate, clarify or confuse, and yet the motive is blind without the direction of awareness. If I know of what I speak, I will not have to make exaggerated gestures or jump up and down. If I comprehend the truth of the matter, I do not require parlor tricks and sleight of hand.

The loftiness of the words will be in purity of their origins; the dignity of speech is a consequence of the wisdom that stands behind it. I have known many people babble on and ramble on about things they know to be untrue, while I don’t think I have ever heard someone fail to make his point if he is sincerely willing to die for it.

Just as form follows function, so style follows character.

As much as I try to learn about contemporary norms of marketing, I am always met with blank faces when I ask about whether they are right or wrong. The most helpful response I ever received was “If it moves the product, you’ve done it right.”

Now I may not agree with the underlying premise, but I respect the honesty. Where some see a spectrum from virtue to vice, others see a difference between riches and poverty.

I’m not sure, however, why the practice of fast talking or the shifty deal should have a place in any model. Where did we get the assumption that profit and candor must be at odds? I suppose it will only happen if we care far more for the former than we do for the latter.

Similarly, I have been called to jury duty far more often than can ever make sense statistically, and each time I have managed to make a fuss.

“Yes, your honor, I do have a bias in this case. Simply by observing how they pander to you, I have a sneaking suspicion that both lawyers involved have the gift of the gab, and I’m pretty sure they will try to pull a fast one on the jury. They are slick and they are quick. I wouldn’t buy a car from either of them, and so I certainly wouldn’t trust them to make a case in a matter of justice.”

Some judges grinned, others yelled at me, but I’ll be damned if I let either fast talking or bullying tell me how to inform my conscience.

Just as a decent man has a hunch when a nude is art and when it is pornography, so a decent man discerns noble rhetoric from disgraceful sophistry. Spending some solid time on the habits of judgment will allow me to catch the fast talker.

Sunday, December 25, 2022

Xenophon, Memorabilia of Socrates 17

Or to take another point. If it appeared to him that a sign from heaven had been given him, nothing would have induced him to go against heavenly warning: he would as soon have been persuaded to accept the guidance of a blind man ignorant of the path to lead him on a journey in place of one who knew the road and could see; and so he denounced the folly of others who do things contrary to the warnings of God in order to avoid some disrepute among men.

The habit and style of living to which he subjected his soul and body was one which under ordinary circumstances would enable anyone adopting it to look existence cheerily in the face and to pass his days serenely: it would certainly entail no difficulties as regards expense.

Seneca, Moral Letters 40.4

May I add that such a jargon of confused and ill-chosen words cannot afford pleasure, either? No; but just as you are well satisfied, in the majority of cases, to have seen through tricks which you did not think could possibly be done, so in the case of these word-gymnasts—to have heard them once is amply sufficient.

For what can a man desire to learn or to imitate in them? What is he to think of their souls, when their speech is sent into the charge in utter disorder, and cannot be kept in hand?

A problem with “fast” speech is not only that it comes so hurriedly, but also that it has no substance behind it, much like fast food. There may be an immediate appeal to the senses, though after an act of voracious consumption there has been no process of nutrition. Yes, the alluring aroma of french fries has something in common with the slick words of the huckster.

Full of sound fury, signifying nothing?

Even as the attraction is supposedly in the instant gratification, it turns out not to be as “fun” as I might have wished. It may arrive with force, and yet it is blunt, and it does not go deep, and it passes as quickly as it came.

After the fleeting diversion, a longing still remains, and while the fool is driven to fall for the same impulse again and again, the wise man has already untangled the cunning illusion. There is no real joy in it, because there is no truth in it.

I neither wish to be like the trickster, who only deals in images, nor do I wish to be his victim, who surrenders his self-control for idle fancies. In either case, there is a betrayal of integrity, such that I wonder if we all know how we are playing one another, but are afraid to finally admit it, to proclaim that the emperor has no clothes.

The example of recklessly running downhill is quite fitting, one I remember from a time when I was oblivious to the prospect of any injury to the body. Now I am more careful about where I step with my feet, and yet I have been slower to learn about the consequences of my ill-chosen words.

A passion points me in a certain direction, and before I know it, I am swept away by my disregard. It is compounded by then feeling indignant and defensive about my blunder, like a cat pretending it meant to run into the glass.

Saturday, December 24, 2022

Friday, December 23, 2022

Thursday, December 22, 2022

Howard Jones, Human's Lib 7

Drowning their sorrows, and mumblin', and forgot the fight

We can tip the balance we can break those barriers down

Little things count as much as the big and turn it all around

And it's oh, don't always look at the rain

No, don't look at the rain

Some people I know have lost their feel for mystery

They say everything has got to be proved, this isn't a nursery

And Joseph who's five years old, stops fights in his playground yard

No more fights and bigotry, oh is it so hard

And it's oh, don't always look at the rain

No, don't always look at the rain

Ha, don't always look at the rain

And tell me, is it a crime to have an ideal or two

Evolving takes it's time, we can't do it all in one go

Doesn't have to drive us all mad, we can only do our best

Let the mind shut up, and the heart do the rest

Wednesday, December 21, 2022

Sayings of Ramakrishna 191

Seneca, Moral Letters 40.3

But I object just as strongly that he should drip out his words as that he should go at top speed; he should neither keep the ear on the stretch, nor deafen it. For that poverty-stricken and thin-spun style also makes the audience less attentive because they are weary of its stammering slowness; nevertheless, the word which has been long awaited sinks in more easily than the word which flits past us on the wing.

Finally, people speak of "handing down" precepts to their pupils; but one is not "handing down" that which eludes the grasp.

Besides, speech that deals with the truth should be unadorned and plain. This popular style has nothing to do with the truth; its aim is to impress the common herd, to ravish heedless ears by its speed; it does not offer itself for discussion, but snatches itself away from discussion.

But how can that speech govern others which cannot itself be governed? May I not also remark that all speech which is employed for the purpose of healing our minds, ought to sink into us? Remedies do not avail unless they remain in the system.

Hold your horses! There is too much, and then there is too little. The Classical model of life understands how the mean lies, sometimes rather precariously, between two extremes. The delicate balance of a virtue is at threat from either side of excess and deficiency.

On the one hand there is the braggart, and on the other there is the boor. I occasionally worry that my Aristotelian and Thomist training gets in the way of my Stoic practice, and then I remember that tribalism has no place in the love of truth.

Am I now more like the tortoise than I am like the hare? I only know I need to get the job done, and I prefer to err on the side of caution instead of rushing in without any due diligence. From speaking like a 33 at 45 rpm, I suppose I have ended up sounding terribly sleepy. I’m still working at it.

Nevertheless, give me the quiet man over the rambling man on any day. I believe it was Emily Dickinson who feared a man of frugal speech, for she feared he might be grand.

Seneca was a man of refined rhetoric, and that is something I have not yet mastered. Will it someday come to me? Perhaps, though I must work on the essentials first. No one can preach with any confidence about the virtues he has not yet mastered; note how often we get the order backwards.

Teachers of all sorts will go on about how well they “personally relate” to their students, and so we have sadly ended up with education as a kind of popularity contest, where the best actors get tenure. I’m now fine with being the tortoise, and having Bugs Bunny laugh at me for my sluggishness.

Remember, slow and steady wins the race. Aiming for character is the only race that matters.

Ah, “mountebank!” Now there’s a word that needs to come back, along with charlatan, scoundrel, caitiff, blackguard, and demagogue. I would even be content with hearing about rascals. When we have no distinction between right and wrong, all the words are reduced to a warm and fuzzy mediocrity.

We’d all like to be saints, without admitting there are any sinners.

Tuesday, December 20, 2022

Monday, December 19, 2022

Stoic Snippets 179

The Wisdom of Solomon 15:18-19

most hateful animals,

which are worse than all others, when judged

by their lack of intelligence;

[19] and even as animals they are not so beautiful

in appearance that one would desire them,

but they have escaped both the praise of God and his blessing.

Seneca, Moral Letters 40.2

"He is wont," you say, "to wrench up his words with a mighty rush, and he does not let them flow forth one by one, but makes them crowd and dash upon each other. For the words come in such quantity that a single voice is inadequate to utter them."

I do not approve of this in a philosopher; his speech, like his life, should be composed; and nothing that rushes headlong and is hurried is well ordered.

That is why, in Homer, the rapid style, which sweeps down without a break like a snowsquall, is assigned to the younger speaker; from the old man eloquence flows gently, sweeter than honey.

I can’t find a single reference to this Serapio, and none of the editions of Seneca’s Letters on my shelf offer any suggestions. That’s quite alright, because philosophy shouldn’t be about becoming famous, for the good philosopher finds his joy in living well, simply for its own sake.

But was Serapio actually a good philosopher? While I should never make that fatal mistake of confusing style with substance, to what extent does the way a man chooses to express himself reflect upon his inner character? The outer appearance is hardly the cause of the inner disposition, though the former can reveal much as an effect proceeding from the latter.

It would seem that Serapio spoke profusely, hurriedly, and sloppily, which is hardly uncommon among those who seek out an audience. While the underlying motives, habits, and circumstances will vary, the presence of lazy language should be a warning to look out for lazy thinking, and if a man has difficulty in ordering his words and actions, there is a good chance he needs to work on ordering his reason.

I obviously can’t speak for Serapio, and so I examine myself. When I was younger, in those hectic teenage years, I had a problem with blurting out the first thing that came into my head. It was only the rigorous exercise of self-reflection that permitted me to slowly adjust this harmful reaction, as I realized that there must be clear apprehension, true judgment, and sound demonstration before there can be any meaningful expression.

If this requires some time, then so be it; those unwilling to wait are probably not ready to listen. I find it odd that people now joke about my moments of silence instead of my passionate interruptions.

Even as I grew older, and it became apparent I was being asked to become a teacher, I noticed how I had a frustrating tendency to speak far too quickly. Now I may have thought an idea over carefully, but there was still a torrent of words once I decided to have my say. It was impossible for anyone to take notes or consider what I was suggesting with all the nervous gushing.

And there was the key, the awareness that my anxiety about being in front of people made me rush through the task of being put on the spot. For all the tricks of rhetoric, what ultimately helped me was learning to manage my fear of a crowd, to accept that my worth did not rise or fall with their smiles or frowns. Speak with patience and charity, but speak the truth. It’s the old Stoic advice: modify the attitude, and you modify the outcome.

Before reading this passage from Seneca, it had never occurred to me how Homer wrote his characters to communicate with such different styles. I now see the pattern more easily, not just in literature but also in daily life, where unbridled passion is frantic and hard-earned wisdom is serene.

A calm and balanced mind will have a calm and balanced voice.