Then I answered her, “Cherisher of all

the virtues, you tell me but the truth. I cannot deny my rapid successes and my

prosperity. But it is such remembrances that torment me more than others. For

of all suffering from Fortune, the unhappiest misfortune is to have known a

happy fortune.”

“But,” said Philosophy, “you are paying

the penalty for your mistaken expectations, and with this you cannot justly

charge your life's circumstances. If you are affected by this empty name of

Fortune's gift of happiness, you must listen while I recall how many and how

great are your sources of happiness. And thus, if you have possessed that which

is the most precious among all Fortune's gifts, and if that is still safe and

unharmed in your possession, you will never, while you keep these better gifts,

be able to justly charge Fortune with unkindness.

“Firstly, your wife's father,

Symmachus, is still living and hale, and what more precious glory has the human

race than him? And he, because your worth is undiminished and your life still

so valuable, is mourning for the injustice you suffer, this man who is wholly

made up of wisdom and virtue.

“Again, your wife lives, a woman whose

character is full of virtue, whose modesty excels its kind, a woman who (to put

in a word the gifts she brought you) is like her father. She lives, and, hating

this life, for your sake alone she clings to it. Herein only will I yield to

allow you unhappiness. She pines with tears and grief through her longing for

you.

“Need I speak of your sons who have

both been consuls, and whose lives, as when they were boys, are yet bright with

the character of their grandfather and their father?

“Wherefore, since mortals desire

exceedingly to keep a hold on life, how happy you should be, if you knew but

your blessings, since you have still what none doubts to be dearer than life

itself? Wherefore now dry your tears. Fortune's hatred has not yet been so

great as to destroy all your holds upon happiness. The tempest that is fallen

upon you is not too great for you. Your anchors hold yet firm, and they should

keep ever nigh to you confidence in the present and hope for future time.” . .

.

—from

Book 2, Prose 4

In reply

to Lady Philosophy’s claim that life has already given him far more of value

than he thinks, Boethius raises a point I have very often considered myself.

The greatest pain, he suggests, is not merely in lacking something good, but in

having once had something good, and then losing it. The haunting memory of a

blessing now gone can seem too much to bear.

I know

this feeling all too well. I will sometimes tell myself that I can still manage

to bear all other sorts of suffering, however painful, but that I cannot seem

to manage the agony of having lost something deeply precious to me. This is

especially the case when it was so joyful and fulfilling at the time, yet I now

know that nothing could ever be done to get it back. I will struggle intensely

to come to terms with the permanent absence of what once was present. It cannot

be recovered.

When my

son was about four years old, he had a toy fighter plane he took everywhere

with him. He once left it sitting on a bench in the playground, and though he

realized he had forgotten it within only a few minutes, it was gone by the time

I ran back to retrieve it. Some other child had surely taken it home. The look

of intense sadness on his face broke my heart, because I wished to spare him

such a sense of loss in life. It seemed such a little thing, but I could tell

how much it weighed on his young mind. No other toy, however fancy, could take

its place. He would never fly it all around the room again, and I would miss

that glowing face he had as he zipped through the house or the yard.

My

father is an incredibly strong man, but one need only mention his old Rover

2000 to bring a tear to his eye. He loved that car so dearly, having picked it

up straight from the factory at Solihull, and driven it all over Europe before

bringing it home to America. The bungling of an incompetent local mechanic

meant he had to give it up, and again, even as it was only a thing, it hurts

him just as much now as it did fifty years ago.

I was

once shattered by the loss of someone I thought of as my dearest friend. It was

not because of any epic circumstances, but simply from being unceremoniously

dropped one day, never to be acknowledged or considered again. I knew I would

have to go on, and I learned deeply from my own life-defining mistake, but not

a day passes where I am not weighed down by a profound sense of irredeemable

loss. The remembrance of things past is the torment.

Lady

Philosophy responds to Boethius, and to all of us who have ever felt this way, that

the problem is never from what happens, but from our expectations about what

happens. Slowly but surely, she is shifting the basic question about happiness

and misery from the power of events to the power of our attitudes about events.

If we ourselves are the ones who decided that Fortune made all the difference,

do we have any right to then double back and question her ways?

She has

already said that if Fortune is measured by a balance sheet of debits and

credits, Boethius would still seem to come out ahead, and now she adds that

while he might have lost things that were valuable to him, the most precious

gifts are still within his reach. After all, doesn’t he still have the shining

example of his father-in-law, the dedication of his wife, and his pride in his

sons?

I have often been frustrated when people advise me that I still have so much, even when I myself feel like I have nothing left to hold on to. I imagine Boethius must be feeling something similar. Though Lady Philosophy is still applying only the mildest temporary relief, and has yet to propose a more powerful cure, she is asking Boethius to begin considering that it isn’t really Fortune who is to blame. After all, we seem to be getting exactly what we asked for when we follow Fortune. Perhaps we should look for something different, something that depends less on different sorts and degrees of receiving and possessing?

I have often been frustrated when people advise me that I still have so much, even when I myself feel like I have nothing left to hold on to. I imagine Boethius must be feeling something similar. Though Lady Philosophy is still applying only the mildest temporary relief, and has yet to propose a more powerful cure, she is asking Boethius to begin considering that it isn’t really Fortune who is to blame. After all, we seem to be getting exactly what we asked for when we follow Fortune. Perhaps we should look for something different, something that depends less on different sorts and degrees of receiving and possessing?

Written in 7/2015

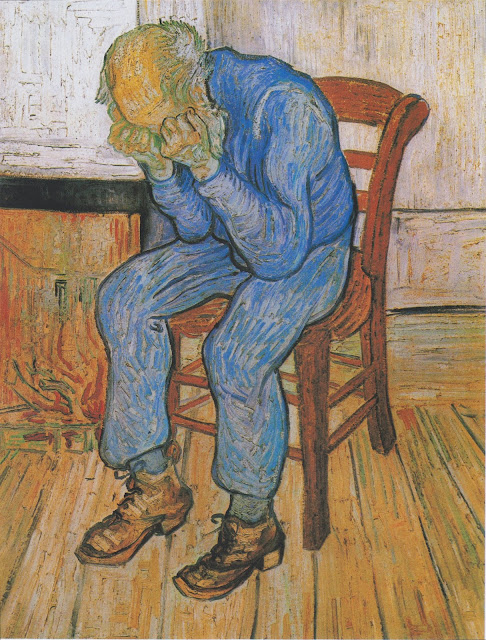

IMAGE: Vincent van Gogh, Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity's Gate) (1890)

No comments:

Post a Comment