M. You may ask, How the case is in peace? What is to be done at home? How we are to behave in bed?

You bring me back to the philosophers, who seldom go to war. Among these, Dionysius of Heraclea, a man certainly of no resolution, having learned fortitude of Zeno, quitted it on being in pain; for, being tormented with a pain in his kidneys, in bewailing himself he cried out that those things were false which he had formerly conceived of pain.

And when his fellow disciple, Cleanthes, asked him why he had changed his opinion, he answered, “That the case of any man who had applied so much time to philosophy, and yet was unable to bear pain, might be a sufficient proof that pain is an evil; that he himself had spent many years at philosophy, and yet could not bear pain: it followed, therefore, that pain was an evil.”

It is reported that Cleanthes on that struck his foot on the ground, and repeated a verse out of the Epigonae:

“Amphiaraus, hear’st thou this below?”

He meant Zeno: he was sorry the other had degenerated from him.

But it was not so with our friend Posidonius, whom I have often seen myself; and I will tell you what Pompey used to say of him: that when he came to Rhodes, after his departure from Syria, he had a great desire to hear Posidonius, but was informed that he was very ill of a severe fit of the gout; yet he had great inclination to pay a visit to so famous a philosopher.

Accordingly, when he had seen him, and paid his compliments, and had spoken with great respect of him, he said he was very sorry that he could not hear him lecture.

“But indeed you may,” replied the other, “nor will I suffer any bodily pain to occasion so great a man to visit me in vain.”

On this Pompey relates that, as he lay on his bed, he disputed with great dignity and fluency on this very subject: that nothing was good but what was honest; and that in his paroxysms he would often say, “Pain, it is to no purpose; notwithstanding you are troublesome, I will never acknowledge you an evil.”

And in general, all celebrated and notorious afflictions become endurable by disregarding them.

You bring me back to the philosophers, who seldom go to war. Among these, Dionysius of Heraclea, a man certainly of no resolution, having learned fortitude of Zeno, quitted it on being in pain; for, being tormented with a pain in his kidneys, in bewailing himself he cried out that those things were false which he had formerly conceived of pain.

And when his fellow disciple, Cleanthes, asked him why he had changed his opinion, he answered, “That the case of any man who had applied so much time to philosophy, and yet was unable to bear pain, might be a sufficient proof that pain is an evil; that he himself had spent many years at philosophy, and yet could not bear pain: it followed, therefore, that pain was an evil.”

It is reported that Cleanthes on that struck his foot on the ground, and repeated a verse out of the Epigonae:

“Amphiaraus, hear’st thou this below?”

He meant Zeno: he was sorry the other had degenerated from him.

But it was not so with our friend Posidonius, whom I have often seen myself; and I will tell you what Pompey used to say of him: that when he came to Rhodes, after his departure from Syria, he had a great desire to hear Posidonius, but was informed that he was very ill of a severe fit of the gout; yet he had great inclination to pay a visit to so famous a philosopher.

Accordingly, when he had seen him, and paid his compliments, and had spoken with great respect of him, he said he was very sorry that he could not hear him lecture.

“But indeed you may,” replied the other, “nor will I suffer any bodily pain to occasion so great a man to visit me in vain.”

On this Pompey relates that, as he lay on his bed, he disputed with great dignity and fluency on this very subject: that nothing was good but what was honest; and that in his paroxysms he would often say, “Pain, it is to no purpose; notwithstanding you are troublesome, I will never acknowledge you an evil.”

And in general, all celebrated and notorious afflictions become endurable by disregarding them.

—from Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 2.25

While I do find great encouragement in a variety of martial examples, I’m afraid I do not possess the disposition of Plato’s Auxiliaries, who are gifted with a particular excellence of the spirited soul. I can be scrappy if I need to be, but I wasn’t born to be much of a brawler.

How is someone to conquer pain without going out on the battlefield? While they hardly appear as grand, the mundane struggles of the everyman are just as real, and overcoming such suffering will be just as critical to finding any happiness. What is the meek, bookish sort expected to do?

To offer some insight on the matter, Cicero tells us about two Stoic philosophers. While both could talk the talk, it ultimately turned out only one of them was willing to walk the walk.

I first read about Dionysius of Heraclea in Diogenes Laërtius, where he is given the unflattering moniker of “the Renegade”. Dionysius at first followed the Stoic School of Zeno, but then became ill, and fled to the hedonist teachings of the Cyrenaics.

Diogenes Laërtius said his disease was in his eyes, while Cicero placed it in his kidneys, but in either case we find a man who could not bring himself to love virtue first, and thus be indifferent to pleasure and pain, on account of concrete suffering.

Diogenes says that Dionysius fell in with a licentious crowd, and eventually took his own life by starvation. His response to Cleanthes speaks volumes about the insidious force of our human weaknesses:

“Look! I’m a trained philosopher, and I couldn’t get a handle on this pain thing, so that means no one has the moxie to do so! Of course pain is an evil, otherwise I would have licked it!”

It just goes to show how even an expert philosopher is prone to putting the cart before the horse.

Let he who is without sin cast the first stone. I fear Dionysius made a terrible mistake, but I am sympathetic with his dilemma. How often have I cried out that my agony was unbearable, cursed the gods, and then barely escaped by some reprieve of fortune, which had absolutely nothing to do with me? Only the steady formation of daily habits has made my current pains tolerable, and still I remain tempted to tap out.

In contrast, Posidonius of Apameia shows me how mistaken I am in underestimating my capacities. I have never suffered from gout, but I am told it is one of the most excruciating ailments there can be. I have read enough history to know of the many aristocrats who dealt with the torture by sitting motionless in a dark and quiet room, drinking themselves into oblivion.

And yet instead of hiding away, Posidonius welcomed the company of Pompey, happy to discuss Stoic philosophy, and he remained firm in his conviction that his pain could do him no harm. Insist upon the primacy of the virtues, in all that you think, say, or do, and then the suffering is transformed from a burden into an opportunity.

So just as the mindset of Dionysius was the cause of his defeat, so the mindset of Posidonius was the cause of his victory. It is as possible on a sickbed as it is on the battlefield.

While I do find great encouragement in a variety of martial examples, I’m afraid I do not possess the disposition of Plato’s Auxiliaries, who are gifted with a particular excellence of the spirited soul. I can be scrappy if I need to be, but I wasn’t born to be much of a brawler.

How is someone to conquer pain without going out on the battlefield? While they hardly appear as grand, the mundane struggles of the everyman are just as real, and overcoming such suffering will be just as critical to finding any happiness. What is the meek, bookish sort expected to do?

To offer some insight on the matter, Cicero tells us about two Stoic philosophers. While both could talk the talk, it ultimately turned out only one of them was willing to walk the walk.

I first read about Dionysius of Heraclea in Diogenes Laërtius, where he is given the unflattering moniker of “the Renegade”. Dionysius at first followed the Stoic School of Zeno, but then became ill, and fled to the hedonist teachings of the Cyrenaics.

Diogenes Laërtius said his disease was in his eyes, while Cicero placed it in his kidneys, but in either case we find a man who could not bring himself to love virtue first, and thus be indifferent to pleasure and pain, on account of concrete suffering.

Diogenes says that Dionysius fell in with a licentious crowd, and eventually took his own life by starvation. His response to Cleanthes speaks volumes about the insidious force of our human weaknesses:

“Look! I’m a trained philosopher, and I couldn’t get a handle on this pain thing, so that means no one has the moxie to do so! Of course pain is an evil, otherwise I would have licked it!”

It just goes to show how even an expert philosopher is prone to putting the cart before the horse.

Let he who is without sin cast the first stone. I fear Dionysius made a terrible mistake, but I am sympathetic with his dilemma. How often have I cried out that my agony was unbearable, cursed the gods, and then barely escaped by some reprieve of fortune, which had absolutely nothing to do with me? Only the steady formation of daily habits has made my current pains tolerable, and still I remain tempted to tap out.

In contrast, Posidonius of Apameia shows me how mistaken I am in underestimating my capacities. I have never suffered from gout, but I am told it is one of the most excruciating ailments there can be. I have read enough history to know of the many aristocrats who dealt with the torture by sitting motionless in a dark and quiet room, drinking themselves into oblivion.

And yet instead of hiding away, Posidonius welcomed the company of Pompey, happy to discuss Stoic philosophy, and he remained firm in his conviction that his pain could do him no harm. Insist upon the primacy of the virtues, in all that you think, say, or do, and then the suffering is transformed from a burden into an opportunity.

So just as the mindset of Dionysius was the cause of his defeat, so the mindset of Posidonius was the cause of his victory. It is as possible on a sickbed as it is on the battlefield.

—Reflection written in 8/1996

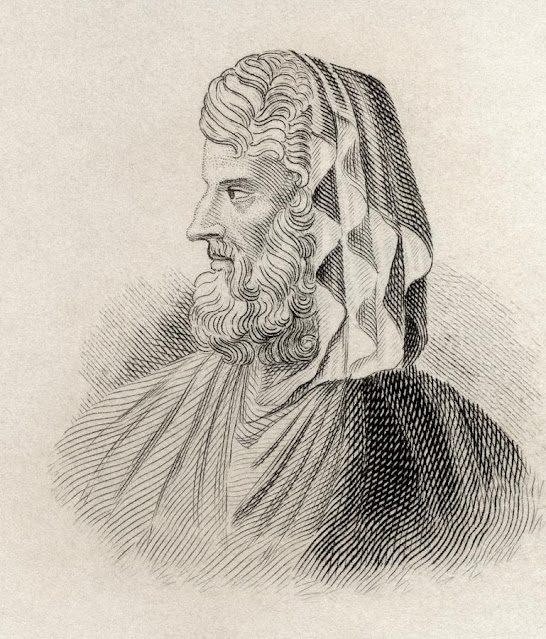

IMAGES: Depictions of Dionysius of Heraclea and Posidonius of Apameia, from Crabbes Historical Dictionary (1825)

No comments:

Post a Comment