A. I do not think virtue can possibly be sufficient for a happy life.

M. But my friend Brutus thinks so, whose judgment, with submission, I greatly prefer to yours.

A. I make no doubt of it; but your regard for him is not the business now: the question is now, what is the real character of that quality of which I have declared my opinion. I wish you to dispute on that.

M. What! Do you deny that virtue can possibly be sufficient for a happy life?

A. It is what I entirely deny.

M. What! Is not virtue sufficient to enable us to live as we ought, honestly, commendably, or, in fine, to live well?

A. Certainly sufficient.

M. Can you, then, help calling any one miserable who lives ill? Or will you deny that anyone who you allow lives well must inevitably live happily?

A. Why may I not? For a man may be upright in his life, honest, praiseworthy, even in the midst of torments, and therefore live well. Provided you understand what I mean by well; for when I say well, I mean with constancy, and dignity, and wisdom, and courage; for a man may display all these qualities on the rack; but yet the rack is inconsistent with a happy life.

M. What, then? Is your happy life left on the outside of the prison, while constancy, dignity, wisdom, and the other virtues, are surrendered up to the executioner, and bear punishment and pain without reluctance?

A. You must look out for something new if you would do any good. These things have very little effect on me, not merely from their being common, but principally because, like certain light wines that will not bear water, these arguments of the Stoics are pleasanter to taste than to swallow.

As when that assemblage of virtues is committed to the rack, it raises so reverend a spectacle before our eyes that happiness seems to hasten on towards them, and not to suffer them to be deserted by her.

But when you take your attention off from this picture and these images of the virtues to the truth and the reality, what remains without disguise is, the question whether anyone can be happy in torment?

Wherefore let us now examine that point, and not be under any apprehensions, lest the virtues should expostulate, and complain that they are forsaken by happiness.

M. But my friend Brutus thinks so, whose judgment, with submission, I greatly prefer to yours.

A. I make no doubt of it; but your regard for him is not the business now: the question is now, what is the real character of that quality of which I have declared my opinion. I wish you to dispute on that.

M. What! Do you deny that virtue can possibly be sufficient for a happy life?

A. It is what I entirely deny.

M. What! Is not virtue sufficient to enable us to live as we ought, honestly, commendably, or, in fine, to live well?

A. Certainly sufficient.

M. Can you, then, help calling any one miserable who lives ill? Or will you deny that anyone who you allow lives well must inevitably live happily?

A. Why may I not? For a man may be upright in his life, honest, praiseworthy, even in the midst of torments, and therefore live well. Provided you understand what I mean by well; for when I say well, I mean with constancy, and dignity, and wisdom, and courage; for a man may display all these qualities on the rack; but yet the rack is inconsistent with a happy life.

M. What, then? Is your happy life left on the outside of the prison, while constancy, dignity, wisdom, and the other virtues, are surrendered up to the executioner, and bear punishment and pain without reluctance?

A. You must look out for something new if you would do any good. These things have very little effect on me, not merely from their being common, but principally because, like certain light wines that will not bear water, these arguments of the Stoics are pleasanter to taste than to swallow.

As when that assemblage of virtues is committed to the rack, it raises so reverend a spectacle before our eyes that happiness seems to hasten on towards them, and not to suffer them to be deserted by her.

But when you take your attention off from this picture and these images of the virtues to the truth and the reality, what remains without disguise is, the question whether anyone can be happy in torment?

Wherefore let us now examine that point, and not be under any apprehensions, lest the virtues should expostulate, and complain that they are forsaken by happiness.

For if prudence is connected with every virtue, then prudence itself discovers this, that all good men are not therefore happy; and she recollects many things of Marcus Atilius, Quintus Caepio, Marcus Aquilius; and prudence herself, if these representations are more agreeable to you than the things themselves, restrains happiness when it is endeavoring to throw itself into torments, and denies that it has any connection with pain and torture.

—from Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 5.5

I enjoy how the Auditor seems to have a little more spunk this time around, willing to dig in his heels on the tension between virtue and happiness. Nor is he merely being stubborn, as he argues for a grounded awareness of the fact that life will not necessarily shower us with blessings, just because we choose to be good. While something may sound fine in the grand theory, it also needs to work in the gritty practice.

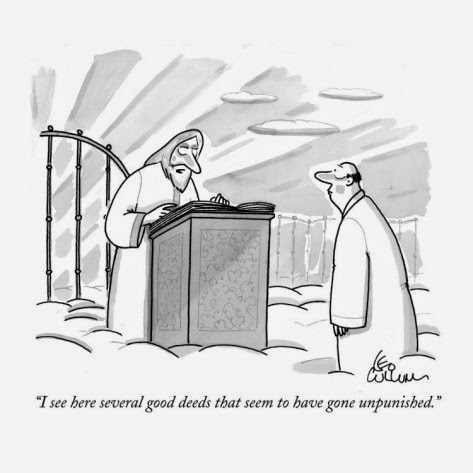

The objection is timeless, for all of us know how doing the right thing does not always feel like the most fulfilling thing. Indeed, we may be tempted to believe that there is even a contradiction between morality and success, that no good deed goes unpunished, that nice guys finish last. While this may not diminish the glory of righteousness, it still means that the man of character has no guarantee of ever being content with his lot.

From the perspective of a philosophy geek, it bears a certain resemblance to the challenge presented by Immanuel Kant: do your duty, whatever the consequences, but don’t expect it to bring you bliss. I can appreciate the heroic gesture, and yet I can’t help but find it tragic. It makes for a fractured world, a world of noble causes and broken hearts.

Now the Auditor is no relativist or hedonist, since he isn’t denying the existence of a higher moral law; he is simply pointing out how some other law appears to decide whether we will be happy. Perhaps there is a reason why the most heroic people end up looking so somber and severe, burdened with pain while they fearlessly cling to their principles.

Observe how Cicero appeals to both authority and shame; were those rhetorical tricks he learned from the teachings of Carneades? The Auditor will have none of it. There is no avoiding the reality that no man can be satisfied while he is being tortured on the rack. Tell me how the holy martyr died with total integrity, and I will remind you how he was also in terrible agony—no reasonable man calls that happiness!

I once knew a psychology student who made a similar claim, and he pointed to saints like Sebastian or Lawrence as instances of sexual masochism, the only possible explanation for finding joy in the midst of suffering. Indeed, how could we think otherwise, if we measure our satisfaction by the presence of pleasure and the absence of pain? But I am getting too far ahead of myself . . .

And the Auditor will not budge after calls upon lofty ideals, insisting that philosophers like the Stoics make it all sound far too easy. Again, this fellow is plucky—might Cicero be deliberately testing his mettle? Whether or not I agree with his conclusions, he presents his case with clarity and conviction, to the point where I find myself nodding my head, equally irritated by the experts pontificating from their cozy armchairs.

If the three examples from Roman history are too obscure, I can immediately think of so many cases closer to home. For every one who finds a life of integrity joined with comfort, there are dozens and dozens who try to be honest and end up in the gutter. I think it no accident that the sleaziest person I know is showered with fame and fortune, while the most decent person I know can never get a break.

Once you remind me of the details about why life doesn’t seem fair, I once again have my doubts. I have sympathy with the Auditor, and I am eager to hear Cicero’s reply.

—Reflection written in 2/1999

No comments:

Post a Comment