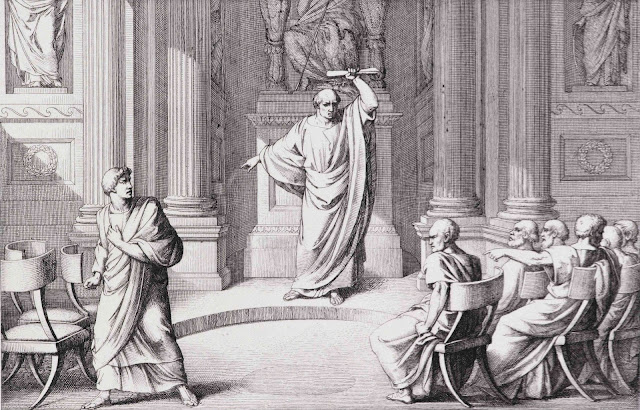

M. Anger is in no wise becoming in an orator, though it is not amiss to affect it. Do you imagine that I am angry when in pleading I use any extraordinary vehemence and sharpness? What! When I write out my speeches after all is over and past, am I then angry while writing?

Or do you think Aesopus was ever angry when he acted, or Accius was so when he wrote? Those men, indeed, act very well, but the orator acts better than the player, provided he be really an orator; but, then, they carry it on without passion, and with a composed mind.

But what wantonness is it to commend lust! You produce Themistocles and Demosthenes; to these you add Pythagoras, Democritus, and Plato. What! Do you then call studies lust? But these studies of the most excellent and admirable things, such as those were which you bring forward on all occasions, ought to be composed and tranquil; and what kind of philosophers are they who commend grief, than which nothing is more detestable? Afranius has said much to this purpose:

“Let him but grieve, no matter what the cause.”

But he spoke this of a debauched and dissolute youth. But we are inquiring into the conduct of a constant and wise man. We may even allow a centurion or standard-bearer to be angry, or any others, whom, not to explain too far the mysteries of the rhetoricians, I shall not mention here; for to touch the passions, where reason cannot be come at, may have its use; but my inquiry, as I often repeat, is about a wise man.

—from Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 4.25

“Oh, what an inspiring man! He speaks with such passion!”

I hear this regularly about politicians, and preachers, and all sorts of celebrities, and while I appreciate it when people are moved, I do wonder what exactly it is that so moves them. If it is the mere presence of intense emotion, then I can think of many men whose wickedness was driven by a fiery rage, and I dare to suggest that the passion is only as good as the principle.

True conviction is about knowing the good, not just about feeling intoxicated. You may scornfully tell me that Nietzsche would disagree, and I will quietly tell you that you may be following the wrong role models.

I am glad to hear Cicero say that anger doesn’t make for a fine speech, unless it is cautiously employed as a rhetorical device. In any case, even if a simulation of outrage is present, it is never itself a cause for confidence. A man who is furious, or horrified, or envious does not even understand himself at that moment, let alone possess any authority to persuade others.

With a few notable exceptions, most of what passes for philosophy among my peers is an exercise in emotional manipulation. I could blame David Hume, for attempting to reduce all meaning and value to the appetites, or Jean-Paul Sartre, for wrapping everything in anxiety and dread, but resentment is hardly the point, since I refuse to restrict myself to my impressions. With Cicero, and with the Stoics, I reach beyond myself through an awareness of my place within Nature, as a creature defined by reason.

So, when they insist that I be lustful in order to be sincere, or depressed in order to be genuine, I will respectfully refuse, because I know that this is not who I was made to be. Your fervor does not intimidate me, though a sign from your conscience would embolden me.

A fellow student once claimed that Plato’s Symposium was one of the greatest texts he had ever read, because it was all about sex. I countered that I believed it to be all about love, and he gave me a puzzled look. “What’s the difference?”

No comments:

Post a Comment