Building upon many years of privately shared thoughts on the real benefits of Stoic Philosophy, Liam Milburn eventually published a selection of Stoic passages that had helped him to live well. They were accompanied by some of his own personal reflections. This blog hopes to continue his mission of encouraging the wisdom of Stoicism in the exercise of everyday life. All the reflections are taken from his notes, from late 1992 to early 2017.

The Death of Marcus Aurelius

Wednesday, January 31, 2024

Tuesday, January 30, 2024

Monday, January 29, 2024

Stockdale on Stoicism 41

Epictetus turned out to be right. All told, it was only a temporary setback from things that were important to me, and being cast in the role as the sovereign head of an American expatriate colony which was destined to remain autonomous, out of communication with Washington, for years on end, was very important to me. I was determined to "play well the given part."

The key word for all of us at first was fragility. Each of us, before we were ever in shouting distance of another American, was made to "take the ropes." That was a real shock to our systems—and as with all shocks, its impact on our inner selves was a lot more impressive and lasting and important than to our limbs and torsos.

These were the sessions where we were taken down to submission and made to blurt out distasteful confessions of guilt and American complicity into antique tape recorders, and then to be put in what I call "cold soak, " six or eight weeks of total isolation to "contemplate our crimes."

What we actually contemplated was what even the most self-satisfied American saw as his betrayal of himself and everything he stood for.

It was there that I learned what "Stoic harm" meant. A shoulder broken, a bone in my back broken, and a leg broken twice were peanuts by comparison.

Epictetus said: "Look not for any greater harm than this: destroying the trustworthy, self-respecting, well-behaved man within you."

When put into a regular cell block, hardly an American came out of that without responding something like this when first whispered to by a fellow prisoner next door: "You don't want to talk to me; I am a traitor."

And because we were equally fragile, it seemed to catch on that we all replied something like this: "Listen, pal, there are no virgins in here. You should have heard the kind of statement I made. Snap out of it. We're all in this together. What's your name? Tell me about yourself."

To hear that last was, for most new prisoners, just out of initial shakedown and cold soak, a turning point in their lives.

—from James B. Stockdale, Master of My Fate: A Stoic Philosopher in a Hanoi Prison

Sayings of Ramakrishna 233

There is always a shade under the lamp while its light illumines the surrounding objects.

So the man in the immediate proximity of a Prophet does not understand him. Those who live afar off are charmed by his spirit and extraordinary power.

Seneca, Moral Letters 64.4

If I meet a consul or a praetor, I shall pay him all the honor which his post of honor is wont to receive: I shall dismount, uncover, and yield the road.

What, then? Shall I admit into my soul with less than the highest marks of respect Marcus Cato, the Elder and the Younger, Laelius the Wise, Socrates and Plato, Zeno and Cleanthes?

I worship them in very truth, and always rise to do honor to such noble names. Farewell.

What, then? Shall I admit into my soul with less than the highest marks of respect Marcus Cato, the Elder and the Younger, Laelius the Wise, Socrates and Plato, Zeno and Cleanthes?

I worship them in very truth, and always rise to do honor to such noble names. Farewell.

—from Seneca, Moral Letters 64

I especially enjoy the closing to this letter, and while I imagine many people will gloss over it as a merely rhetorical conclusion, I dwell upon it for a moment to remind myself of how important it is to practice sincere reverence.

I once expected both theologians and philosophers to be filled with awe for the true, the good, and the beautiful, and yet I sadly found that most of them were too busy bickering with their colleagues, their smug faces and dismissive sneers betraying an enslavement to their “professional” pride. I now make it a point to avoid such petty vanities as best I possibly can.

In all walks of life, we immediately wish to be respected by others, but find it quite difficult to offer them respect in return. I therefore force myself, each morning when I wake, to reflect upon what I properly owe, not upon what I feel I am owed. A genuine piety, whether it be for institutions, for people, or ultimately for God, is only possible for me when I recognize why I am not the center and measure of all things.

What is equal cannot exist outside of what is also greater or lesser. We do ourselves a disservice when we focus on the horizontal at the expense of the vertical.

How can I expect to become better, if I foolishly believe I am already the best? Philosophy points me to universal and necessary principles that give meaning and purpose to all of reality, and so it is right for me to defer to them. By bowing down to what is greater than myself, I thereby also become most fully myself.

Even as I can be quite the annoying radical, and I will not hesitate to cross the man who considers himself to be entitled, I am also quite happy to show honor when it is surely due. If you have earned a position, you have my submission; if you have achieved great deeds, you have my admiration. As long as it isn’t just about the show, it is fitting to freely give way to my superiors.

And if it is suitable to show respect for a worldly station, how much more I am called to respect those who serve the glory of the soul! I owe everything of value in my life to the gifts of wisdom and virtue, and so the teachers of wisdom and virtue are the highest in my esteem.

My Catholic friends might not be happy calling it worship, or even veneration, so let’s just stick with reverence. I am afraid that a man who cannot revere is accordingly incapable of any of the other virtues, for he acknowledges nothing beyond his own self-conceit.

I especially enjoy the closing to this letter, and while I imagine many people will gloss over it as a merely rhetorical conclusion, I dwell upon it for a moment to remind myself of how important it is to practice sincere reverence.

I once expected both theologians and philosophers to be filled with awe for the true, the good, and the beautiful, and yet I sadly found that most of them were too busy bickering with their colleagues, their smug faces and dismissive sneers betraying an enslavement to their “professional” pride. I now make it a point to avoid such petty vanities as best I possibly can.

In all walks of life, we immediately wish to be respected by others, but find it quite difficult to offer them respect in return. I therefore force myself, each morning when I wake, to reflect upon what I properly owe, not upon what I feel I am owed. A genuine piety, whether it be for institutions, for people, or ultimately for God, is only possible for me when I recognize why I am not the center and measure of all things.

What is equal cannot exist outside of what is also greater or lesser. We do ourselves a disservice when we focus on the horizontal at the expense of the vertical.

How can I expect to become better, if I foolishly believe I am already the best? Philosophy points me to universal and necessary principles that give meaning and purpose to all of reality, and so it is right for me to defer to them. By bowing down to what is greater than myself, I thereby also become most fully myself.

Even as I can be quite the annoying radical, and I will not hesitate to cross the man who considers himself to be entitled, I am also quite happy to show honor when it is surely due. If you have earned a position, you have my submission; if you have achieved great deeds, you have my admiration. As long as it isn’t just about the show, it is fitting to freely give way to my superiors.

And if it is suitable to show respect for a worldly station, how much more I am called to respect those who serve the glory of the soul! I owe everything of value in my life to the gifts of wisdom and virtue, and so the teachers of wisdom and virtue are the highest in my esteem.

My Catholic friends might not be happy calling it worship, or even veneration, so let’s just stick with reverence. I am afraid that a man who cannot revere is accordingly incapable of any of the other virtues, for he acknowledges nothing beyond his own self-conceit.

—Reflection written in 7/2013

IMAGE: John William Waterhouse, The Shrine (1895)

Sunday, January 28, 2024

Saturday, January 27, 2024

Stoic Snippets 226

A spider is proud when it has caught a fly, and another when he has caught a poor hare, and another when he has taken a little fish in a net, and another when he has taken wild boars, and another when he has taken bears, and another when he has taken Sarmatians.

Are not these robbers, if you examine their opinions?

—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 10.10

IMAGE: William Allan, Tartar Robbers Dividing Spoil (1817)

Friday, January 26, 2024

Henry David Thoreau 1

When will the world learn that a million men are of no importance compared with one man?

—Henry David Thoreau, in a letter to Ralph Waldo Emerson (June 8, 1843)

Ralph Waldo Emerson 5

Self-reliance, the height and perfection of man, is reliance on God.

—from Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Fugitive Slave Law

IMAGE: Jan Bruegel the Younger, The Creation of Adam (c. 1650)

Thursday, January 25, 2024

Dhammapada 360, 361

Restraint in the eye is good, good is restraint in the ear, in the nose restraint is good, good is restraint in the tongue.

In the body restraint is good, good is restraint in speech, in thought restraint is good, good is restraint in all things.

A Bhikshu, restrained in all things, is freed from all pain.

Seneca, Moral Letters 64.3

But even if the old masters have discovered everything, one thing will be always new—the application and the scientific study and classification of the discoveries made by others.

Assume that prescriptions have been handed down to us for the healing of the eyes; there is no need of my searching for others in addition; but for all that, these prescriptions must be adapted to the particular disease and to the particular stage of the disease.

Use this prescription to relieve granulation of the eyelids, that to reduce the swelling of the lids, this to prevent sudden pain or a rush of tears, that to sharpen the vision. Then compound these several prescriptions, watch for the right time of their application, and apply the proper treatment in each case.

The cures for the spirit also have been discovered by the ancients; but it is our task to learn the method and the time of treatment.

Assume that prescriptions have been handed down to us for the healing of the eyes; there is no need of my searching for others in addition; but for all that, these prescriptions must be adapted to the particular disease and to the particular stage of the disease.

Use this prescription to relieve granulation of the eyelids, that to reduce the swelling of the lids, this to prevent sudden pain or a rush of tears, that to sharpen the vision. Then compound these several prescriptions, watch for the right time of their application, and apply the proper treatment in each case.

The cures for the spirit also have been discovered by the ancients; but it is our task to learn the method and the time of treatment.

Our predecessors have worked much improvement, but have not worked out the problem. They deserve respect, however, and should be worshipped with a divine ritual. Why should I not keep statues of great men to kindle my enthusiasm, and celebrate their birthdays? Why should I not continually greet them with respect and honor?

The reverence which I owe to my own teachers I owe in like measure to those teachers of the human race, the source from which the beginnings of such great blessings have flowed.

—from Seneca, Moral Letters 64

I am equally wary of the stuffy traditionalist, who obsesses about the distant past as if it had been some glorious paradise, and the fiery progressive, who latches on to every new trend as if it proves the base ignorance of his forefathers. Both of them are too enamored with the narrow part of their preferences; neither of them are open to the harmony of the whole.

I should have the humility to recognize how those who came before me had the benefit of facing our common challenges first, and so they offer us the gift of handing down their accumulated understanding. As I myself grow older, and hopefully just a little bit wiser, I return back to those venerable insights I had once overlooked, shocked by how fresh they suddenly seem.

And yet none of this means that the work is already complete, or that the truth is cast in stone. The Universe is far too vast to be grasped by one man, or even by one age, and even if the Ancients had managed to isolate all the essentials, there would still be no end to discovering the peculiarities of the craft. As Seneca says, it is one thing to write a sweeping theory of medicine, and quite another to become a skillful physician.

Perhaps the tradition has granted me the breadth, and now I must engage in exploring the depths, as only I can do for myself, in these unique conditions. This may be the correct prescription, but what is the best dosage or frequency? Though you can pass me a handbook, I will still have to learn in the field. The theory, however nobly expressed, needs to be fleshed out in gritty practice.

Along with Seneca, I thank God for the wisdom of old, also knowing full well that Providence is now asking me to do my half, to be my own particular instance of the universal, to apply what is eternally true for all to what is now true for me. That process will unfold for all time, as the very order and design of Nature intends. Wisdom is thereby continually reborn.

I am equally wary of the stuffy traditionalist, who obsesses about the distant past as if it had been some glorious paradise, and the fiery progressive, who latches on to every new trend as if it proves the base ignorance of his forefathers. Both of them are too enamored with the narrow part of their preferences; neither of them are open to the harmony of the whole.

I should have the humility to recognize how those who came before me had the benefit of facing our common challenges first, and so they offer us the gift of handing down their accumulated understanding. As I myself grow older, and hopefully just a little bit wiser, I return back to those venerable insights I had once overlooked, shocked by how fresh they suddenly seem.

And yet none of this means that the work is already complete, or that the truth is cast in stone. The Universe is far too vast to be grasped by one man, or even by one age, and even if the Ancients had managed to isolate all the essentials, there would still be no end to discovering the peculiarities of the craft. As Seneca says, it is one thing to write a sweeping theory of medicine, and quite another to become a skillful physician.

Perhaps the tradition has granted me the breadth, and now I must engage in exploring the depths, as only I can do for myself, in these unique conditions. This may be the correct prescription, but what is the best dosage or frequency? Though you can pass me a handbook, I will still have to learn in the field. The theory, however nobly expressed, needs to be fleshed out in gritty practice.

Along with Seneca, I thank God for the wisdom of old, also knowing full well that Providence is now asking me to do my half, to be my own particular instance of the universal, to apply what is eternally true for all to what is now true for me. That process will unfold for all time, as the very order and design of Nature intends. Wisdom is thereby continually reborn.

—Reflection written in 7/2013

IMAGE: Gustav Klimt, Pallas Athena (1898)

Wednesday, January 24, 2024

Tuesday, January 23, 2024

Ellis Walker, Epictetus in Poetical Paraphrase 47

XLVII.

When you're inform'd that any one thro' spight

Or an ill-natur'd, scurrilous delight

Of railing, slanders you, or doth accuse

Of doing something base, or scandalous,

Disquiet not yourself for an excuse,

Nor, blust'ring, swear he wrongs you with a lye,

But slight th' abuse, and make this calm reply:

"Alas! he's ignorant! for had he known

My other faults and follies, he had shewn

Those too, nor had he spoke of this alone."

Or an ill-natur'd, scurrilous delight

Of railing, slanders you, or doth accuse

Of doing something base, or scandalous,

Disquiet not yourself for an excuse,

Nor, blust'ring, swear he wrongs you with a lye,

But slight th' abuse, and make this calm reply:

"Alas! he's ignorant! for had he known

My other faults and follies, he had shewn

Those too, nor had he spoke of this alone."

Seneca, Moral Letters 64.2

I want something to overcome, something on which I may test my endurance. For this is another remarkable quality that Sextius possesses: he will show you the grandeur of the happy life and yet will not make you despair of attaining it; you will understand that it is on high, but that it is accessible to him who has the will to seek it.

And virtue herself will have the same effect upon you, of making you admire her and yet hope to attain her. In my own case, at any rate the very contemplation of wisdom takes much of my time; I gaze upon her with bewilderment, just as I sometimes gaze upon the firmament itself, which I often behold as if I saw it for the first time.

Hence, I worship the discoveries of wisdom and their discoverers; to enter, as it were, into the inheritance of many predecessors is a delight. It was for me that they laid up this treasure; it was for me that they toiled. But we should play the part of a careful householder; we should increase what we have inherited. This inheritance shall pass from me to my descendants larger than before.

Much still remains to do, and much will always remain, and he who shall be born a thousand ages hence will not be barred from his opportunity of adding something further.

And virtue herself will have the same effect upon you, of making you admire her and yet hope to attain her. In my own case, at any rate the very contemplation of wisdom takes much of my time; I gaze upon her with bewilderment, just as I sometimes gaze upon the firmament itself, which I often behold as if I saw it for the first time.

Hence, I worship the discoveries of wisdom and their discoverers; to enter, as it were, into the inheritance of many predecessors is a delight. It was for me that they laid up this treasure; it was for me that they toiled. But we should play the part of a careful householder; we should increase what we have inherited. This inheritance shall pass from me to my descendants larger than before.

Much still remains to do, and much will always remain, and he who shall be born a thousand ages hence will not be barred from his opportunity of adding something further.

—from Seneca, Moral Letters 64

Some time ago, I grew tired of constantly being told to work harder, and I worried that this betrayed some fatal flaw in my character. Why could I not bring myself to putting in the extra effort? Yet then I realized that it wasn’t grueling labor that bothered me at all, but rather the waste of committing myself to empty prizes, the false premise that jumping through hoops and accumulating more trinkets would make me happy.

When I allow myself to understand what is truly valuable in this life, then I am glad to go through hell and high water to achieve my goal. Please don’t insist, however, that I will become blessed by being your wage slave, while still remaining perpetually in debt so I can buy more products I don’t actually need.

It helps me so greatly to have someone like a Quintus Sextius urging me on, to show me both the glory that can be mine and to assure me of why such an end is certainly within my power to achieve.

Far too often, the self-appointed saviors will make the task appear as nigh impossible, and then they conveniently demand a total surrender to their wishes as the only remedy. The true philosopher, the man who sees you as a friend and not as a customer, has a faith in your own capacity for excellence.

Wisdom can appear quite lofty, even haughty, and I may wonder if a dull fellow like me has it in him to appreciate her subtleties. But once I have introduced myself, I find that she asks for nothing more than integrity and fidelity, and her teachings about my nature are not complex or cryptic at all, as long as I don’t puff myself up with pride.

I have often overlooked what she has to say, because I thought I had to start from scratch, to reinvent the wheel. No, I don’t need to go it alone; those who came before me have already lit the way. In contrast to the modernists, who believe everything must always be new, I am quite content to rely upon what is timeless.

For every obstacle I face, for every pain I encounter, I am sure to find someone who has already been there, and has already done that. I am not alone.

I suppose I’m sounding stuffier as I get older, but there is a certain security in knowing that the Ancients had already grappled with all the problems of this life, and we are just building on the foundation they built. Though I laughed at it back then, I now respect what was meant when they told me that all later philosophy was just a footnote to Plato.

Though wisdom always grows in each new generation, it’s all from the same seed. Though virtue speaks in different languages, she is an expression of one and the same universal good.

Some time ago, I grew tired of constantly being told to work harder, and I worried that this betrayed some fatal flaw in my character. Why could I not bring myself to putting in the extra effort? Yet then I realized that it wasn’t grueling labor that bothered me at all, but rather the waste of committing myself to empty prizes, the false premise that jumping through hoops and accumulating more trinkets would make me happy.

When I allow myself to understand what is truly valuable in this life, then I am glad to go through hell and high water to achieve my goal. Please don’t insist, however, that I will become blessed by being your wage slave, while still remaining perpetually in debt so I can buy more products I don’t actually need.

It helps me so greatly to have someone like a Quintus Sextius urging me on, to show me both the glory that can be mine and to assure me of why such an end is certainly within my power to achieve.

Far too often, the self-appointed saviors will make the task appear as nigh impossible, and then they conveniently demand a total surrender to their wishes as the only remedy. The true philosopher, the man who sees you as a friend and not as a customer, has a faith in your own capacity for excellence.

Wisdom can appear quite lofty, even haughty, and I may wonder if a dull fellow like me has it in him to appreciate her subtleties. But once I have introduced myself, I find that she asks for nothing more than integrity and fidelity, and her teachings about my nature are not complex or cryptic at all, as long as I don’t puff myself up with pride.

I have often overlooked what she has to say, because I thought I had to start from scratch, to reinvent the wheel. No, I don’t need to go it alone; those who came before me have already lit the way. In contrast to the modernists, who believe everything must always be new, I am quite content to rely upon what is timeless.

For every obstacle I face, for every pain I encounter, I am sure to find someone who has already been there, and has already done that. I am not alone.

I suppose I’m sounding stuffier as I get older, but there is a certain security in knowing that the Ancients had already grappled with all the problems of this life, and we are just building on the foundation they built. Though I laughed at it back then, I now respect what was meant when they told me that all later philosophy was just a footnote to Plato.

Though wisdom always grows in each new generation, it’s all from the same seed. Though virtue speaks in different languages, she is an expression of one and the same universal good.

—Reflection written in 7/2013

IMAGE: Jacob de Wit, Truth and Wisdom Assist History in Writing (1754)

Monday, January 22, 2024

Maxims of Goethe 33

There are two powers that make for peace: what is right, and what is fitting.

IMAGE: Jan Lievens, Allegory of Peace (1652)

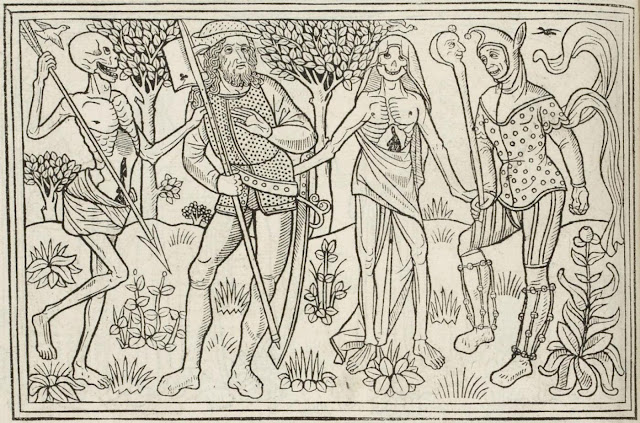

William Hogarth, A Rake's Progress 6

Accordingly, I can't relate directly to Tom's obsession, but I can certainly turn to examples of my own peculiar fixations to understand how quickly an object of desire can enslave my powers of reason and choice. Furthermore, I know all too well how my distorted perceptions can make me believe that, despite the experience of one disaster after another, this next time will somehow be magically different.

The gamblers are so absorbed in their addiction that they do not even notice how a fire has broken out. Tom, with his wig discarded, raises his fist to Heaven, for like so many who are seduced by sin, he is surely convinced that God is to blame for his failure. I am all too familiar with the feeling that Fortune has wronged me, when all along I have only wronged myself.

A highwayman, identifiable by the pistol and the mask in his pocket, drinks to forget his losses, while another fellow bites his nails in torment. A man who has just lost pulls his hat over his eyes. Two men are pleased with their ill-gotten gains, while two other men are in the midst of a dispute. A well-dressed gentleman borrows from a loan shark, who might remind the viewer of Tom's father.

A mad dog reflects the hysteria of the entire scene. Is it safe to say that Tom has now used up all the possible escapes from his foolhardiness? For a man who has thought of nothing but acquiring money, what will become of him now that his wealth is finally gone for good?

William Hogarth, A Rake's Progress VI: The Gaming House (1734)

Sunday, January 21, 2024

Delphic Maxims 44

Educate your sons

IMAGE: Pietro della Vecchia, Know Thyself: Socrates and Two Students (c. 1650)

Saturday, January 20, 2024

James Vila Blake, Sonnets from Marcus Aurelius 13

13.

Τοῖς μὲν ἀλόγοις ζῴοις καὶ καθόλου πράγμασι καὶ ὑποκειμένοις, ὡς λόγον ἔχων λόγον μὴ ἔχουσι, χρῶ μεγαλοφρόνως καὶ ἐλευθέρως: τοῖς δὲ ἀνθρώποις, ὡς λόγον ἔχουσι, χρῶ κοινωνικῶς: ἐφ̓ ἅπασι δὲ θεοὺς ἐπικαλοῦ. καὶ μὴ διαφέρου πρὸς τὸ πόσῳ χρόνῳ ταῦτα πράξεις: ἀρκοῦσι γὰρ καὶ τρεῖς ὧραι τοιαῦται.

—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 6.23

13.

My mute or unbrogued fellows, as speechless so,

And thus but little reasoned; and let this bar

Incline me to reason for them, high for low.

We talk with reasons to reasons, being men;

But Nature’s birds and brooks, tree-fingering breeze,

Gaunt roars, compound my voice. Be it my ken

To hold in reasoning love fellows like these.

For this seek help. Is any wise alone?

Let each give aid, and then all seek to God,

Commingled in petitionary tone

That moves to one what ’s near or far abroad.

For time, each hath enough to do his part.

Moments but few are mighty, flamed with heart.

IMAGE: Giovanni Bellini, The Feast of the Gods (1514)

Sayings of Ramakrishna 232

The seeds of Vagravântula do not fall to the bottom of the tree. From the shell they shoot far away from the tree and take root there.

So the Spirit of a Prophet manifests itself at a distance, and he is appreciated there.

Seneca, Moral Letters 64.1

Letter 64: On the philosopher’s task

Yesterday you were with us. You might complain if I said "yesterday" merely. This is why I have added "with us." For, so far as I am concerned, you are always with me. Certain friends had happened in, on whose account a somewhat brighter fire was laid—not the kind that generally bursts from the kitchen chimneys of the rich and scares the watch, but the moderate blaze which means that guests have come.

Our talk ran on various themes, as is natural at a dinner; it pursued no chain of thought to the end, but jumped from one topic to another. We then had read to us a book by Quintus Sextius the Elder. He is a great man, if you have any confidence in my opinion, and a real Stoic, though he himself denies it.

Ye Gods, what strength and spirit one finds in him! This is not the case with all philosophers; there are some men of illustrious name whose writings are sapless. They lay down rules, they argue, and they quibble; they do not infuse spirit simply because they have no spirit.

But when you come to read Sextius, you will say: "He is alive; he is strong; he is free; he is more than a man; he fills me with a mighty confidence before I close his book."

I shall acknowledge to you the state of mind I am in when I read his works: I want to challenge every hazard; I want to cry: "Why keep me waiting, Fortune? Enter the lists! Behold, I am ready for you!" I assume the spirit of a man who seeks where he may make trial of himself, where he may show his worth:

“And fretting 'mid the unwarlike flocks he prays

Some foam-flecked boar may cross his path, or else

A tawny lion stalking down the hills."

Yesterday you were with us. You might complain if I said "yesterday" merely. This is why I have added "with us." For, so far as I am concerned, you are always with me. Certain friends had happened in, on whose account a somewhat brighter fire was laid—not the kind that generally bursts from the kitchen chimneys of the rich and scares the watch, but the moderate blaze which means that guests have come.

Our talk ran on various themes, as is natural at a dinner; it pursued no chain of thought to the end, but jumped from one topic to another. We then had read to us a book by Quintus Sextius the Elder. He is a great man, if you have any confidence in my opinion, and a real Stoic, though he himself denies it.

Ye Gods, what strength and spirit one finds in him! This is not the case with all philosophers; there are some men of illustrious name whose writings are sapless. They lay down rules, they argue, and they quibble; they do not infuse spirit simply because they have no spirit.

But when you come to read Sextius, you will say: "He is alive; he is strong; he is free; he is more than a man; he fills me with a mighty confidence before I close his book."

I shall acknowledge to you the state of mind I am in when I read his works: I want to challenge every hazard; I want to cry: "Why keep me waiting, Fortune? Enter the lists! Behold, I am ready for you!" I assume the spirit of a man who seeks where he may make trial of himself, where he may show his worth:

“And fretting 'mid the unwarlike flocks he prays

Some foam-flecked boar may cross his path, or else

A tawny lion stalking down the hills."

—from Seneca, Moral Letters 64

Of all the things I find myself missing, I have a special longing for a good conversation. I once assumed that I simply had to go out and find one, but the unfortunate fact is that an engaging dialogue requires genuine friends, and both sometimes seem to be as rare as hen’s teeth.

The Stoic stress on self-reliance can mislead me into believing that I should be content to go it alone, and yet the equal Stoic stress on fellowship then reminds me how we are all made for one another. For all the grief that comes with struggling to love, there are still those redeeming moments when the human bond expresses itself precisely as it should.

As elusive as it may feel, some excellent company is a powerful inspiration to the formation of an excellent character. If those of us gathered around the table are hardly the wisest or most virtuous of men, we can at least aspire to become so, for even the slightest step forward is moving us in the right direction. And if the topic of conversation is the example of some better man, then we may participate vicariously.

I don’t know any surviving texts by Quintus Sextius, but the way Seneca describes the effects of his teachings reminds of the handful of fine folks who have offered me profound hope and strength through the many years of doubt and hesitation.

Almost all of those who advertised themselves as “philosophers” may have had a knack for playing about with words, and yet I would walk away from their fancy speeches with only a headache and an urge to sleep. In contrast, the true philosophers, who never claimed the title, fired me up with the urgency of becoming a kinder and braver man, right now, before it is too late.

No, they didn’t just take a hold of my passions, for that is merely a fleeting power; instead, they challenged me to think for myself, and to see myself for who I truly was, behind all the intellectual posturing. By presenting me with the sharp contrast between who I could be and how I managed to fall so terribly short, I suddenly had the wind behind my sails.

Of all the things I find myself missing, I have a special longing for a good conversation. I once assumed that I simply had to go out and find one, but the unfortunate fact is that an engaging dialogue requires genuine friends, and both sometimes seem to be as rare as hen’s teeth.

The Stoic stress on self-reliance can mislead me into believing that I should be content to go it alone, and yet the equal Stoic stress on fellowship then reminds me how we are all made for one another. For all the grief that comes with struggling to love, there are still those redeeming moments when the human bond expresses itself precisely as it should.

As elusive as it may feel, some excellent company is a powerful inspiration to the formation of an excellent character. If those of us gathered around the table are hardly the wisest or most virtuous of men, we can at least aspire to become so, for even the slightest step forward is moving us in the right direction. And if the topic of conversation is the example of some better man, then we may participate vicariously.

I don’t know any surviving texts by Quintus Sextius, but the way Seneca describes the effects of his teachings reminds of the handful of fine folks who have offered me profound hope and strength through the many years of doubt and hesitation.

Almost all of those who advertised themselves as “philosophers” may have had a knack for playing about with words, and yet I would walk away from their fancy speeches with only a headache and an urge to sleep. In contrast, the true philosophers, who never claimed the title, fired me up with the urgency of becoming a kinder and braver man, right now, before it is too late.

No, they didn’t just take a hold of my passions, for that is merely a fleeting power; instead, they challenged me to think for myself, and to see myself for who I truly was, behind all the intellectual posturing. By presenting me with the sharp contrast between who I could be and how I managed to fall so terribly short, I suddenly had the wind behind my sails.

The lovers or the politicians might ask you to die for them, while the sages can explain why you should be willing to die for yourself. When the dignity of the soul is at stake, no trifling threat to the body can stand in the way.

—Reflection written in 7/2013

IMAGE: Peter Paul Rubens, Samson Killing the Lion (1628)

Friday, January 19, 2024

Stoic Snippets 225

Whatever may happen to you, it was prepared for you from all eternity; and the implication of causes was from eternity spinning the thread of your being, and of that which is incident to it.

—Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 10.5

Thursday, January 18, 2024

Wednesday, January 17, 2024

Tuesday, January 16, 2024

Monday, January 15, 2024

Plutarch, The Life of Cato the Younger 15

When Cato arrived, however, Deiotarus offered him gifts of every sort, and by tempting and entreating him in every way so exasperated him that, although he had arrived late in the day and merely spent the night, on the next day about the third hour he set off.

However, after proceeding a day's journey, he found at Pessinus more gifts again awaiting him than those he had left behind him, and a letter from the Galatian begging him, if he did not desire to take them himself, at least to permit his friends to do so, since they were in every way worthy to receive benefits on his account, and Cato's private means would not reach so far.

But not even to these solicitations did Cato yield, although he saw that some of his friends were beginning to weaken and were disposed to blame him; nay, he declared that every taking of gifts could find plenty of excuse, but that his friends should share in what he had acquired honorably and justly. Then he sent his gifts back to Deiotarus.

As he was about to set sail for Brundisium, his friends thought that the ashes of Caepio should be put aboard another vessel; but Cato declared that he would rather part with his life than with those ashes, and put to sea.

And verily we are told that, as chance would have it, he had a very dangerous passage, although the rest made the journey with little trouble.

IMAGE: Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, The Deceitfulness of Riches (1901)

Dhammapada 356-359

The fields are damaged by weeds, mankind is damaged by passion: therefore a gift bestowed on the passionless brings great reward.

The fields are damaged by weeds, mankind is damaged by hatred: therefore a gift bestowed on those who do not hate brings great reward.

The fields are damaged by weeds, mankind is damaged by vanity: therefore a gift bestowed on those who are free from vanity brings great reward.

The fields are damaged by weeds, mankind is damaged by lust: therefore a gift bestowed on those who are free from lust brings great reward.

IMAGE: Jules Breton, The Weeders (1868)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

_-_Tartar_Robbers_Dividing_Spoil_-_N00373_-_National_Gallery.jpg)