It

is silly to want your children and your wife and your friends to live forever,

for that means that you want what is not in your control to be in your control,

and what is not your own to be yours.

In

the same way if you want your servant to make no mistakes, you are a fool, for

you want vice not to be vice but something different.

But

if you want not to be disappointed in your will to get, you can attain to that.

Exercise

yourself then in what lies in your power. Each man's master is the man who has

authority over what he wishes or does not wish, to secure the one or to take

away the other. Let him then who wishes to be free not wish for anything or

avoid anything that depends on others; or else he is bound to be a slave.

—Epictetus,

The Handbook, Chapter 14 (tr

Matheson)

I have

on a number of occasions tried to explain to others, in the most direct ways I

can find, that Stoicism is not a philosophy one needs to be terribly gifted or

educated to understand. It isn’t the principles themselves that offer me any

obstacles, but my own habits and the pressures of social conformity that can

make it difficult to practice. I just need to take off the blinders, though

that can be easier said than done.

One of

my quick summaries goes something like this, and I’m really just paraphrasing

what Epictetus says above: “If I make myself dependent on the things I can’t

control, I’ll be a slave, and I’ll be frustrated and miserable. If I make

myself dependent on the things I can control, I’ll be my own master, and I can

be free and happy.”

At those

few times when my attempts at an explanation actually sink in, I usually see an

immediate response of recognition. “Yeah, that makes total sense, and I’ve

heard people say things like that before. They were usually the most humble and

happy people I ever knew.” I may then hear a lovely recollection of a relative

or neighbor who was surely a Stoic, regardless of whether he had read

Epictetus.

The

habits of corporate America were already creeping into higher education when I

was a student, and I began to recognize certain formulas that were being used

to “build the brand”. One of these was what I called the mock interview, where

an employee confidently and cheerfully answers a certain set questions to help

the consumer see the human side of the company.

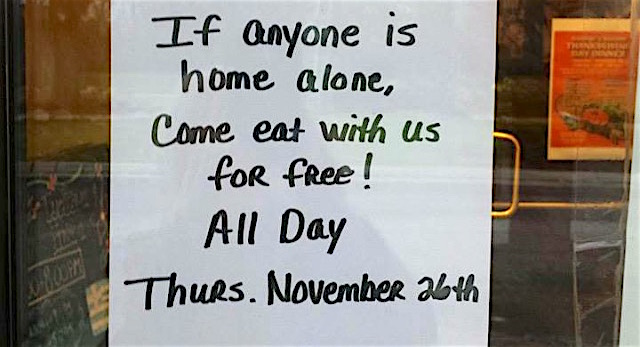

I have

to smile when I see one of those questions: “If you could pick one thing you

wish you could do more of, what would that be?” I then expect one of two

answers: “I’d like to do more to help the community,” and “I’d spend more time

with my wonderful family.”

I knew a

fellow in marketing a few years back who was proudly showing me one of these

pieces online, so I finally asked what the Stoic in me always wanted to ask. I

asked him why he just didn’t spend more time with his family, if that’s what he

really wanted. What was holding him back?

“Well,

my work just keeps me so busy, all the hours and all the travel, so I just

can’t be with them as much as I want. I don’t really have a choice, do I? But I

guess I’m doing it for them, so they can live in a nice house, and the kids can

go to a good school, and they’ll have some security when I’m gone.”

For

once, I didn’t press the Socratic point, because I judged it would do more harm

than good, but I did think about it for myself.

If I

think something is the most important thing I should be doing, I should simply

be doing it. If I think something is getting in the way of what is most

important, I need to leave the obstacle behind.

What is

the good I can leave for my family? Love or money? If the latter is getting in

the way of the former, I obviously can’t pursue both equally. If something,

like the pursuit of a career, is taking control over what I should truly want,

then I’m not really choosing my own life, but allowing others to choose it for

me.

All of

this then makes me honestly ask myself if I really do want mastery and freedom,

a life where my control over my own conviction and character come first, or

whether I am still hiding under the illusion that I will be happier as a slave to

all those things outside of my power.

We all

face that challenge, and how we respond to it will make all the difference.

Marillion, some of my musical heroes, put it this way:

These chains are all your own

These chains are comfortable

This cage was never locked

Born free but scared to be

This cage was made for you

With care and constant attention

This cage is safe and warm

Will you die and never know what it's

like

Outside?

Written in 3/2004