He said that he himself would never prosecute anyone for personal injury nor recommend it to anyone else who claimed to be a philosopher. For actually none of the things which people fancy they suffer as personal injuries are an injury or a disgrace to those who experience them, such as being reviled or struck or spit upon.

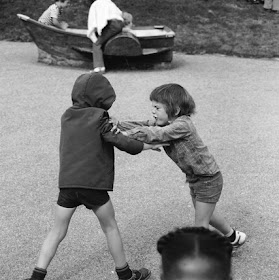

Children can do both truly wonderful and truly horrible things, and in this they are only little instances of all of human nature. When I was five years old, our family moved to a new home in a new neighborhood, and I had before me the exciting but frightening prospect of seeing if I could come across some new friends.

It would be an early lesson about the good and the

bad in people, about discovering kindness in some and malice in others, though

I don’t really know if it was a relief or a frustration to see that folks, both

young and old alike, were really all made of the same stuff. I could already

discern something about the same patterns, popping up over and over from place

to place and from time to time.

My new little corner of the world had an odd quirk,

however, one that has vividly stuck in my memory now for many years. If

children, in quite the range of ages, started arguing with too much gusto, the

whole conversation would break down. The aggrieved parties would retreat back

to the confines of their own yards and continue to yell loudly at one another

from a distance.

“Don’t you dare come onto my property! If you do, I’ll

sue you! I’ll sue you!” This was often accompanied by wild gestures, indicating

the limits of said domains. When I asked my parents about this ritual, they

rolled their eyes and mumbled something about how we had become a “litigious

society”. I didn’t understand what they meant then, but I most certainly do

now.

Whether it be the children bickering around the

neighborhood, or the adults fighting it out in the office buildings downtown,

the tendency is all too familiar. It may begin with whispered gossip, continue

with insults and raised voices, and perhaps even proceed to the trading of blows.

The grown-ups, of course, tend to frown upon physical force, so they may appeal

to other more subtle, but equally violent, means of doing harm. Instead of

punching you in the face, they can make sure you never find work again.

When all these avenues have been exhausted, and the

anger is still not satisfied, people are tempted to appeal to a higher judgment.

They complain to a superior, or report it to the authorities, or bring it to the

law courts. God tends to advise forgiveness, so He will not be of much use

here, though a misguided clergyman can certainly help you exact your revenge,

if you are so inclined.

And revenge is really what it all too easily ends

up being about, inflicting hurt when we feel that we have been hurt. We may

call it justice, or the rule of law, or righting a wrong, but I wonder if what

we often really intend is retaliation, the imposition of force, or outdoing one

wrong with another wrong.

We can indeed debate the specifics of the terms, but

we can know the real difference by looking into our own hearts and minds, by

asking ourselves what we really wish to achieve: is it to find a benefit for

all, or is to seek a benefit for some through a harm to others?

Instead of an accusation, or a lawsuit, or a

condemnation being an absolute last resort, it becomes a casual routine. Instead

of a punishment being a form of restoring balance, it becomes an expression of contempt.

Instead of seeking to reform the offender, we take satisfaction in destroying

him.

The Stoic avoidance of vengeance begins with the

realization that, as social creatures, we are all made for one another, not to stand

in opposition to one another. Yet it goes even further than that, by reminding

us that so many of the things we perceive as insults, offenses, or injuries need

not really do us any deeper harm at all. Why should we feel resentment for what

only hurts us if we ourselves allow it to do so?

Yes, a man may damage my property, or weaken my

reputation, or bring pain on my body, and he himself indeed commits a wrong by

doing so, but he only affects what is on the outside of me, not what is on the

inside of me. He has gravely damaged his own soul, even as mine can remain intact.

Where is the greater hurt? His vice does not need to become mine, as long as I

do not respond with hatred.

Once again, the Stoic Turn involves far more than just

tweaking or rearranging our usual customs; it asks us to rebuild all our

judgments from the bottom up, to never meet evil with evil, and to always take control

over whether or not we decide to take offense.

Written in 10/1999

No comments:

Post a Comment