Building upon many years of privately shared thoughts on the real benefits of Stoic Philosophy, Liam Milburn eventually published a selection of Stoic passages that had helped him to live well. They were accompanied by some of his own personal reflections. This blog hopes to continue his mission of encouraging the wisdom of Stoicism in the exercise of everyday life. All the reflections are taken from his notes, from late 1992 to early 2017.

Reflections

Primary Sources

Saturday, November 30, 2024

Dio Chrysostom, On Kingship 2.1

Friday, November 29, 2024

Wisdom from the Early Cynics, Diogenes 32

Thursday, November 28, 2024

Wisdom from the Early Stoics, Zeno of Citium 72

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

Songs of Innocence 2

From the morn to the evening he strays;

He shall follow his sheep all the day

And his tongue shall be filled with praise.

For he hears the lambs innocent call,

And he hears the ewes tender reply.

He is watchful while they are in peace,

For they know when their Shepherd is nigh.

Seneca, Moral Letters 72.6

They should be shut out; if they once gain an entrance, they will bring in still others to take their places. Let us resist them in their early stages. It is better that they shall never begin than that they shall be made to cease. Farewell.

What would the world be like if we spent far less time on the business of making money, and far more time on the philosophy of building the virtues? It is so tempting to daydream about an ideal society, singing along to some rousing tune about universal solidarity.

And then I remember that while Providence gazes at us from the top down, she always does her work from the bottom up. It is fitting to appreciate the bigger picture, but my first responsibility is to improve myself, for the harmony of the whole is only achieved by the actions of the particular parts. If I wish to change the world, let me begin by putting my own house in order.

How could it be otherwise? As creatures of reason and will, our deeds will proceed from our personal judgments, not from any grand abstractions about politics, economics, or sociology. A man is free, not a machine. Some will choose to strive for wisdom, and others will choose to remain in ignorance, and a good number will also struggle in that dreadful gray area, hesitant to commit.

Find the sort of individual person you wish to be, and take your stand, and then you will have made your mark. You will be cooperating with Providence either way, for all things are ultimately in service to the good, but in one case you will cooperate in joy and in peace, and in another case you will be little more than a foil, dragged along while kicking and screaming.

A man who is continually at the mercy of his circumstances may feel elated at one moment, and then despondent the next, simply because he has failed to establish his measure, to be anchored by the stability of his character. Happiness flows from a constancy of moral purpose, something that the chaos of worldly business can never provide, being so entangled in avarice, deception, and manipulation.

So, if I desire to fix anything at all, I am called to fix myself. Perhaps another will take inspiration, and then he might fix himself as well. Perhaps another will take offense, and then I might have all the more opportunity to put my money where my mouth is. I only know that my first job is to become a good man, not to become a rich man.

Tuesday, November 26, 2024

Monday, November 25, 2024

Dhammapada 391

Seneca, Moral Letters 72.5

"Did you ever see a dog snapping with wide-open jaws at bits of bread or meat which his master tosses to him? Whatever he catches, he straightway swallows whole, and always opens his jaws in the hope of something more.

“So it is with ourselves; we stand expectant, and whatever Fortune has thrown to us we forthwith bolt, without any real pleasure, and then stand alert and frantic for something else to snatch."

But it is not so with the wise man; he is satisfied. Even if something falls to him, he merely accepts it carelessly and lays it aside.

The happiness that he enjoys is supremely great, is lasting, is his own. Assume that a man has good intentions, and has made progress, but is still far from the heights: the result is a series of ups and downs; he is now raised to heaven, now brought down to earth.

For those who lack experience and training, there is no limit to the downhill course; such a one falls into the Chaos of Epicurus—empty and boundless.

There is still a third class of men—those who toy with wisdom; they have not indeed touched it, but yet are in sight of it, and have it, so to speak, within striking distance. They are not dashed about, nor do they drift back either; they are not on dry land, but are already in port.

What usually passes for business, without much reflection, is little more than the accumulation of profit. Philosophy, of course, is given no consideration whatsoever, because when have wisdom or virtue ever increased our wealth, fame, or gratification? Observe very carefully where a man places his priorities, and you will learn fairly quickly whether he is guided by character or by convenience, ruled by love or by lust.

The poor dog cannot help himself, and he depends on receiving proper training from his master, but a man can most certainly help himself, since his reason grants him the power to be his own master. It is natural for the former to be determined by his instincts alone, while it is unnatural for the latter to act without the direction of understanding.

I do wish the writings of Attalus had survived, for one can clearly sense the profound impact his teachings had on Seneca. I suspect he was a bit rougher around the edges than his more refined student, perhaps a kindred spirit to Musonius Rufus, and I can immediately relate to his example of the human devolving into the bestial. I know exactly how it feels to be enslaved by the mindless desire to consume, a craving that can sadly never come to any completion.

Once I define myself by grasping for external satisfaction, I have trapped myself in an endless cycle of wanting ever more and more, since nothing from Fortune can fulfill the internal perfection of Nature. A surefire sign of this obsession is my constant need to consume voraciously, without any appreciation or joy, and quickly move on the next conquest. How could it ever be enough, when I am attempting to satisfy an essential need with some accidental greed?

If, however, it is truly mine, then nothing can ever be added, and nothing can ever be taken away. Some will see the wise man, and because of their own grasping habits, will assume that he is cold and unfeeling. No, he is at peace with himself, and so he does not clamor for treats and trinkets: he understands why his vocation is to be human, not to be a hustler.

If I continue to be tossed about by my circumstances, I have failed to know myself, remaining focused on business instead of philosophy. Even when some progress has been made in self-awareness, there will be that intensely frustrating state of standing “in between”, convinced in part of a need for a radical transformation, but still hesitant to take the final step. I must not permit this to let me relapse into my mindless habits—the difficulty is itself a mark of improvement, which cannot be achieved without growing pains.

I am not yet wise, though I have perceived just enough of the benefits from wisdom that I am no longer a mere brute, that I am called to so much more. Courage!

Sunday, November 24, 2024

Xenophon, Memorabilia of Socrates 35

Socrates: "It would be monstrous on the part of any one who sought to become a general to throw away the slightest opportunity of learning the duties of the office. Such a person, I should say, would deserve to be fined and punished by the state far more than the charlatan who without having learnt the art of a sculptor undertakes a contract to carve a statue.

With arguments like these he persuaded the young man to go and take lessons. After he had gone through the course he came back, and Socrates proceeded playfully to banter him.

Socrates: "Behold our young friend, sirs, as Homer says of Agamemnon, of mein majestical, so he; does he not seem to move more majestically, like one who has studied to be a general?

Then the young man: "He began where he ended; he taught me tactics—tactics and nothing else."

"Yet surely,"replied Socrates, "that is only an infinitesimal part of generalship. A general must be ready in furnishing the material of war: in providing the commissariat for his troops; quick in devices, he must be full of practical resource; nothing must escape his eye or tax his endurance; he must be shrewd, and ready of wit, a combination at once of clemency and fierceness, of simplicity and of insidious craft; he must play the part of watchman, of robber; now prodigal as a spendthrift, and again close-fisted as a miser, the bounty of his munificence must be equalled by the narrowness of his greed; impregnable in defense, a very daredevil in attack—these and many other qualities must he possess who is to make a good general and minister of war; they must come to him by gift of nature or through science.

"The simile is very apt, Socrates," replied the youth, "for in battle, too, the rule is to draw up the best men in front and rear, with those of inferior quality between, where they may be led on by the former and pushed on by the hinder."

Socrates: "Very good, no doubt, if the professor taught you to distinguish good and bad; but if not, where is the use of your learning? It would scarcely help you, would it, to be told to arrange coins in piles, the best coins at top and bottom and the worst in the middle, unless you were first taught to distinguish real from counterfeit."

The Youth: "Well no, upon my word, he did not teach us that, so that the task of distinguishing between good and bad must devolve on ourselves."

Socrates: "Well, shall we see, then, how we may best avoid making blunders between them?"

"I am ready," replied the youth.

Socrates: "Well then! Let us suppose we are marauders, and the task imposed upon us is to carry off some bullion; it will be a right disposition of our forces if we place in the vanguard those who are the greediest of gain?"

Socrates: "Then what if there is danger to be faced? Shall the vanguard consist of men who are greediest of honor?"

The Youth: "It is these, at any rate, who will face danger for the sake of praise and glory. Fortunately such people are not hid away in a corner; they shine forth conspicuous everywhere, and are easy to be discovered."

Socrates: "But tell me, did he teach you how to draw up troops in general, or specifically where and how to apply each particular kind of tactical arrangement?"

The Youth: "Nothing of the sort."

Socrates: "And yet there are and must be innumerable circumstances in which the same ordering of march or battle will be out of place."

The Youth: "I assure you he did not draw any of these fine distinctions."

"He did not, did not he?" he answered. "Bless me! Go back to him again, then, and ply him with questions; if he really has the science, and is not lost to all sense of shame, he will blush to have taken your money and then to have sent you away empty."

Man's Search for Meaning 11

Beatings occurred on the slightest provocation, sometimes for no reason at all.

Saturday, November 23, 2024

Seneca, Moral Letters 72.4

If the latter does not take heed, there is an immediate relapse and a return to the same old trouble; but the wise man cannot slip back, or slip into any more illness at all.

For health of body is a temporary matter which the physician cannot guarantee, even though he has restored it; nay, he is often roused from his bed to visit the same patient who summoned him before. The mind, however, once healed, is healed for good and all.

I shall tell you what I mean by health: if the mind is content with its own self; if it has confidence in itself; if it understands that all those things for which men pray, all the benefits which are bestowed and sought for, are of no importance in relation to a life of happiness; under such conditions it is sound.

For anything that can be added to is imperfect; anything that can suffer loss is not lasting; but let the man whose happiness is to be lasting, rejoice in what is truly his own.

When I was still a young pup, my mother made a point of keeping me home from school for at least one extra day after I had overcome a fever, to make certain I could build up my strength. This annoyed the teachers to no end, since they were enslaved by their lesson plans, and any absence would make a mess of their sacred statistics, but she wouldn’t budge, insisting that health mattered far more than bureaucracy.

When I later became a teacher, I noticed how students were far too careless about getting sick, and so they all spent much the of the year in sort of a state of semi-illness, never quite recovered, and forever prone to the next wave of infections, because they had actually lost sight of what it even meant to be healthy. One half of the room was always sniffling, while the other half was always coughing.

I must never confuse feeling a “bit better” with being cured, and that applies to the spirit as much as it does to the flesh. All too often, I have made the slightest bit of progress, and then hastily assumed that the work was done, only to find myself right back where I started, and perhaps in an even worse place, on account of the shame I felt from my failure. Once bitten, twice shy.

Health is not being free from obstacles, but rather possessing the capacity to cope with obstacles, and so just as the body resists a disease, so the mind overcomes its circumstances. The relapse is unfortunately a sign that the work was not complete, when the expectation has rushed ahead of the reality, and the careful discipline of preparation is the best remedy against disappointment.

I know all too well how the body is continually subject to corruption, and so I will be inclined to believe that the mind must be just the same, yet I am forgetting how the soul is subject only to its own judgments, as long as it remains firm in its own convictions. While disease may slowly but surely take hold of what is on the outside, a man has the power to remain invincible on the inside, according to his choice.

This is why the “Stoic Sage” is not some figment of the imagination—nothing can hinder him except himself. He will face hardships, and he will confront temptations, and he will be racked with doubts, while through it all he knows that he can rise above anything Fortune might throw his way.

Friday, November 22, 2024

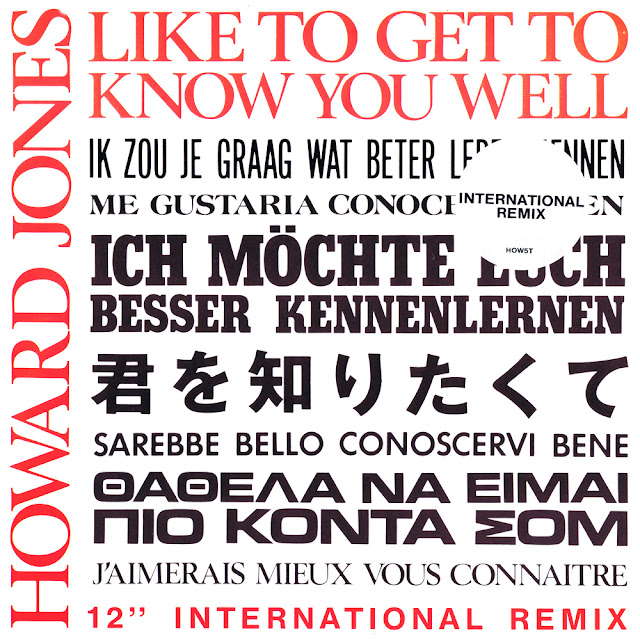

Howard Jones, Dream into Action 14

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

So we can be one

We can be one together

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

So we can be one

We can be one together

Together we can cast away the fear

Together we can wipe away the tear

Together we can strip down the barriers

And be one

Don't wanna talk about the weather

Don't wanna talk about the news

Just wanna get to the real you inside

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

So we can be one

We can be one together

Don't you think now is the time

We should be feelin'

Just wanna simply say

Won't let you slip away

People wanna talk about the future

Don't wanna linger on the past

Just wanna reach to the real you inside

Forget cold glances and rejections

Leave the things that separate

Build on a trust that we can stand on

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

So we can be one

We can be one together

Finding all are insecure

Opening the same door

Leaving out a stubborn pride

Seeing from another side

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

Like to get to know you well

So we can be one

We can be one together

Thursday, November 21, 2024

Seneca, Moral Letters 72.3

He says: "Something will happen to hinder me."

No, not in the case of the man whose spirit, no matter what his business may be, is happy and alert. It is those who are still short of perfection whose happiness can be broken off; the joy of a wise man, on the other hand, is a woven fabric, rent by no chance happening and by no change of fortune; at all times and in all places he is at peace.

For his joy depends on nothing external and looks for no boon from man or fortune. His happiness is something within himself; it would depart from his soul if it entered in from the outside; it is born there.

Sometimes an external happening reminds him of his mortality, but it is a light blow, and merely grazes the surface of his skin. Some trouble, I repeat, may touch him like a breath of wind, but that Supreme Good of his is unshaken.

This is what I mean: there are external disadvantages, like pimples and boils that break out upon a body which is normally strong and sound; but there is no deep-seated malady.

We may assume that pragmatism demands a stress on the action, with a little time left over for some contemplation during the lulls in business, and yet this actually ends up being quite an unrealistic view of life.

No, the mind is constantly aware, so that the only question is whether our knowledge is sound or unsound, critical or lazy; the doing is constantly informed by the thinking, the hands being guided by a sense of meaning and purpose, for better or for worse.

I’m afraid that when “study” has become some sort of afterthought, as if I were cramming the night before the exam, or is reduced to a mere indulgence, tacked on for when it is convenient, I am sorely confused about who I am.

I need mindfulness at all times and in all things, to provide the very merit to those deeds, just as the attentive driver remembers to never take his hands from the wheel. I appreciate this image more and more, as I observe my fellow commuters on the road of life diverted by mobile phones, newspapers, or the consumption of elaborate meals.

My anxiety about what may or may not happen, and my sense of surprise when I slam into the car in front of me, are a consequence of my carelessness. Indeed, I can hardly predict the vagaries of fortune, and yet I always have it within my power to prepare myself, and to rely upon the strength of my own virtues. That I fret over the circumstances is proof of how I have failed to rightly distinguish the good from the bad.

Back in college, I would have sudden attacks of eczema, which were sometimes so severe that my face was transformed into a swollen, burning mess. I was already sensitive enough about my appearance, and this would drive me to despair about going out in public. The doctors never seemed to figure it out, and it eventually went away of its own accord, but the image remains with me as a lesson about priorities.

As Seneca says, the shell on the outside is being battered, while the dignity and the beauty on the inside can still remain constant; do what you will with the body, and the soul may shine all the more. I now think back to the feeling of that itching skin as a symbol of how a steady state of reflection is the key to a peace of mind.

_object_05_The_Shepherd.jpg)

.jpg)