Building upon many years of privately shared thoughts on the real benefits of Stoic Philosophy, Liam Milburn eventually published a selection of Stoic passages that had helped him to live well. They were accompanied by some of his own personal reflections. This blog hopes to continue his mission of encouraging the wisdom of Stoicism in the exercise of everyday life. All the reflections are taken from his notes, from late 1992 to early 2017.

Reflections

▼

Primary Sources

▼

Thursday, May 31, 2018

Some Stoic resources, however meager. . .

Over on the sidebar for the Stoic Breviary blog, you will find a list of twenty or so texts that might be of use for some. These aren't Liam Milburn ramblings, but the original writings that inspired them.

Always best to go straight to the source.

Now these are mainly old editions, all in the public domain, and the formatting and editing are hardly ideal, sometimes even atrocious. They are, however, at the very least, a resource to begin with.

Included are works by Cicero, Seneca, Musonius Rufus, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, Boethius, Justus Lipsius, and some talks given by Stockdale.

More texts, either directly Stoic or indirectly related to Stoicism, will be added as time permits.

Not all of us have a fancy library where we can look things up, and Stoicism should never be a fancy philosophy. We don't necessarily need to be in with the latest scholarship to think and live like real Stoics.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5.8

Just

as we must understand when it is said, that Asclepius prescribed to this man

horse-exercise, or bathing in cold water, or going without shoes, so we must

understand it when it is said, that the nature of the Universe prescribed to

this man disease, or mutilation, or loss or anything else of the kind.

For

in the first case prescribed means something like this: he prescribed this for

this man as a thing adapted to procure health. And in the second case it means:

That which happens to every man is fixed in a manner for him suitably to his

destiny.

For

this is what we mean when we say that things are suitable to us, as the workmen

say of squared stones in walls or the pyramids, that they are suitable, when

they fit them to one another in some kind of connection. For there is

altogether one fitness, one harmony.

And

as the Universe is made up out of all bodies to be such a body as it is, so out

of all existing causes necessity is made up to be such a cause as it is. And

even those who are completely ignorant understand what I mean, for they say, destiny

brought this to such a person. This then was brought and this was prescribed to

him. Let us then receive these things, as well as those that Asclepius

prescribes.

Many,

as a matter of course, among even his prescriptions are disagreeable, but we

accept them in the hope of health. Let the perfecting and accomplishment of the

things, which the common Nature judges to be good, be judged by you to be of

the same kind as your health. And so accept everything that happens, even if it

seems disagreeable, because it leads to this, to the health of the Universe and

to the prosperity and felicity of Zeus.

For

he would not have brought on any man what he has brought, if it were not useful

for the whole. Neither does the nature of anything, whatever it may be, cause anything

that is not suitable to that which is directed by it.

For

two reasons then it is right to be content with that which happens to you. The

one, because it was done for you and prescribed for you, and in a manner had

reference to you, originally from the most ancient causes spun with your

destiny. The other, because even that which comes severally to every man is to

the power which administers the Universe a cause of felicity and perfection,

even of its very continuance.

For

the integrity of the whole is mutilated, if you cut off anything whatever from

the conjunction and the continuity either of the parts or of the causes. And you

do cut off, as far as it is in your power, when you art dissatisfied, and in a

manner try to put anything out of the way.

—Marcus

Aurelius, Meditations, Book 5 (tr

Long)

This

passage from Marcus Aurelius was for me, quite literally, a lifesaver. I happened

upon it at a time when I was in such pain that I could not make it through the

day without collapsing into uncontrollable sobbing. People try to tell us that

it will get better, and that it will all end up for the best. They surely mean

well, but that is of little comfort when the suffering is crippling. But

instead of just patting me on the back and tossing out a phrase that tells me

my situation will change, Marcus Aurelius explains himself. He tells me why whatever happens always happens for

a reason, and always happens because it is good both for me and for the whole

world.

It isn’t

even about wanting to change the situation, but understanding that any

situation can always be a source of benefit, if it is only understood and

applied rightly.

In the

words of Ovid:

Endure and persist; this pain

will one day do good for you.

The

passage helped me to apply the Stoic Turn in a profound way, and reading it

suddenly and unexpectedly gave me a whole new perspective. It didn’t make the

pain cease, but it gave me the means to find purpose within it. That moment

wasn’t, of course, the end of the story, even as it was the beginning of the

story.

It all

revolves around the central Stoic principle that we are not measured by our

circumstances, however extreme they may be. We are measured by our own

thoughts, choices, and actions about those circumstances. Instead of dwelling

on what was coming at me from outside, I could rather ask how what came at me

from outside could be transformed into something different on the inside. My

task wasn’t merely to suffer; my task was to discover how to find benefit for

myself through that suffering.

If I

came to recognize that the only thing that was unconditionally good for me was

my character, then I could ask myself how the things that were happening could

help to build that character, and in turn give me peace and joy. There were

many things I hated about the world, and many more things that I hated about

myself, but the only thing I ever found of value within myself was my ability,

however meager, to love. And it dawned on me that whatever love was within now

me had only been nurtured through my grief. If pain had not broken my cynicism

and disdain, my heart would still have been smothered and neglected.

The very

quality I treasured within me had come about from suffering. What seemed so bad

had been so good all along. I had, without even fully understanding it at the

time, made something worthwhile out of something painful.

This was

true for me, and also for everything around me. Once I began to understand that

the world is not a series of random and unconnected events, I also began to

understand that every cause and every effect, and every part within the whole,

is precisely where it is meant to be. Everything plays its own distinct role,

the good within each thing serving the good of all things.

I had to

smile when I put the book down, because I realized I hadn’t even happened upon

the passage at all. I had been meant to read it from long before I was even

born. It was another small step in finding the path I needed to follow for

myself.

When

Asclepius, the god of medicine, or just my neighborhood doctor, prescribes a

cure, it isn’t always going to be pleasant. Sometimes it will seem worse than

the disease. But the doctor prescribes medicine to help us become healthy, just

as Providence prescribes our circumstances to help us become better, wiser, and

happier.

Written in 3/2006

Wednesday, May 30, 2018

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5.7

A

prayer of the Athenians: Rain, rain, O dear Zeus, down on the ploughed fields

of the Athenians and on the plains.

In

truth we ought not to pray at all, or we ought to pray in this simple and noble

fashion.

—Marcus

Aurelius, Meditations, Book 5 (tr

Long)

I am

always hesitant to discuss prayer, or religion, precisely because it is both so

powerful and so personal. Stoicism, however, is very much a “big tent”

philosophy, and Stoic thinking can be of great assistance in however we may choose

to understand God.

Prayer,

in the broadest sense of our communication with the Divine, can surely be a

profound means of relating ourselves to what is absolute, but it can also be

fraught with danger. Prayer can be a humble expression of praise, thanksgiving,

or supplication. It can also too easily become twisted into a form of showmanship,

vanity, or bargaining.

How easy

it is to turn prayer into a spectacle. I know something has gone wrong when a

prayer becomes a performance, something made public instead of private, a way to

excite the passions and manipulate the thinking of others.

How easy

it is to turn prayer into a worship of the self. I know something has gone

wrong when a prayer is suddenly about man dwelling on his own importance, about

making himself seem big, instead of making himself a part of what is bigger.

How easy

it is to turn prayer into a means for getting what I desire. I know something

has gone wrong when a prayer is an arrogant attempt to make things exist only

for our gratification, and no longer a respect for Providence.

I have

always kept in mind the insight that prayer isn’t something that is supposed to

change God, but rather something that is supposed to change the way I relate

myself to God. From a Stoic perspective, it is never within my power to

determine Providence, even as it is always within my power to freely participate with

Providence.

Don’t

give me what I think I want. Give me what You know I need. A prayer is not

something to which I should add my own conditions, as if I was negotiating a

sale. There’s a good reason I was taught as a child to pray with only four

simple words: “Thy will be done.”

I think

of all the people I have known who have turned their prayer into a mockery, and

I think of all the times I have come far too close to doing the same myself. I

once knew someone for whom God suddenly appeared after she had already decided

something; it was quite amazing how He would miraculously communicate His

agreement with her.

I once knew someone else whose prayers always seemed to be a way to degrade anyone he disagreed with, and for whom religion was nothing more than an expression of an ideology for the privileged, a war between “us” and “them”. “Do it my way” and “slay my enemies” are hardly dignified prayers.

I once knew someone else whose prayers always seemed to be a way to degrade anyone he disagreed with, and for whom religion was nothing more than an expression of an ideology for the privileged, a war between “us” and “them”. “Do it my way” and “slay my enemies” are hardly dignified prayers.

If I do choose

to pray, my prayer should be simple and noble, and never designed to impress

others, glorify myself, or make demands of anyone or anything. As Marcus

Aurelius says, I should limit myself to being open to receive, and to be

grateful for, what Nature has to give.

Written in 3/2006

Tuesday, May 29, 2018

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5.4

I

go through the things which happen according to Nature until I shall fall and

rest, breathing out my breath into that element out of which I daily draw it

in, and falling upon that earth out of which my father collected the seed, and

my mother the blood, and my nurse the milk. Out of which during so many years I

have been supplied with food and drink, which bears me when I tread on it and

abuse it for so many purposes.

—Marcus

Aurelius, Meditations, Book 5 (tr

Long)

When I

seek to live according to Nature, I need to remember that this is not merely a

romantic notion, or a noble abstraction, or an intellectual luxury, or some

pleasant diversion from the business of the day. It is the very business of the day, the stuff itself out of which I am

made, to which I am connected, and to which I will return. To embrace Nature,

as it is understood by the Stoic, is never to turn away from everyday living,

but to finally embrace the fullness of everyday living.

As much

as our human endeavors often seem to mask it, everything that we are is

inseparable from the order of Nature, and even our most impressive artificial

posturing would be nothing separately of that harmony. The part has no meaning

without the whole.

I often

notice how strong and independent we think we are, and though we might be quite

adept at this in our time of high technology and social engineering, this was

surely true for the Rome of Marcus Aurelius as well. We eat, drink, breathe,

and consume or manipulate all sorts of the things around us, quite oblivious to

all the deeper relations between them. We pursue our careers and the

improvement of our position in life, quite oblivious to our very human purpose,

and the depth of our bond with other persons.

I think

it is no accident that the same man who pays no attention to the air he

breathes is quite often the same man who pays no attention to the dignity of

his neighbor. He pollutes the one with his waste, and pollutes the other with

his greed.

The

tools of power and vanity only give the illusion of independence. We are just

as bound to everything and everyone else as we have always been. It is

fortunate that Nature is patient with our tantrums and abuses.

The

tension of this passage by Marcus Aurelius, between being necessarily joined to

the unity of all things on the one hand, and my stubborn insistence on breaking

myself away from that unity on the other, or between being in Nature and yet stepping on it, brings to mind my favorite poem,

which I never miss the opportunity to share:

“God’s

Grandeur”

Gerard Manley

Hopkins

The

world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It

will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It

gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed.

Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations

have trod, have trod, have trod;

And

all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And

wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is

bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And

for all this, nature is never spent;

There

lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And

though the last lights off the black West went

Oh,

morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs—

Because

the Holy Ghost over the bent

World

broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Monday, May 28, 2018

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5.6

One

man, when he has done a service to another, is ready to set it down to his

account as a favor conferred.

Another

is not ready to do this, but still in his own mind he thinks of the man as his

debtor, and he knows what he has done.

A

third in a manner does not even know what he has done, but he is like a vine

that has produced grapes, and seeks for nothing more after it has once produced

its proper fruit.

As

a horse when he has run, a dog when he has tracked the game, a bee when it has

made the honey, so a man when he has done a good act, does not call out for

others to come and see, but he goes on to another act, as a vine goes on to

produce again the grapes in season.

Must

a man then be one of these, who in a manner act thus without observing it? Yes,

but this very thing is necessary, the observation of what a man is doing. For,

it may be said, it is characteristic of the social animal to perceive that he

is working in a social manner, and indeed to wish that his social partner also

should perceive it.

It

is true what you say, but you do not rightly understand what is now said. And

for this reason you will become one of those of whom I spoke before, for even

they are misled by a certain show of reason. But if you will choose to

understand the meaning of what is said, do not fear that for this reason you will

omit any social act.

—Marcus

Aurelius, Meditations, Book 5 (tr

Long)

The good

or bad within my actions will come not only from what I do, but also from the

disposition with which I do it. Merit is not only in the deed, but also in its

relationship to the doer.

Some

people will expect payment for an act of kindness, which, of course, ceases to

make it a kindness. It is actually a transaction. I should be able to recognize

such people immediately, because they will always attach conditions to the

giving of their gifts, which now makes them investments, and terms for their

promises, which now makes them contracts.

When the

good of another becomes a means for my own profit, this is no longer really a

good deed.

Other

people may not demand any external compensation in return, so I may more

readily think of this as an expression of sincerity. I should not so quickly

deceive myself. They are also seeking something else in return, an internal

sense of thinking well of themselves, of self-praise, of importance and

superiority, It is what my great-grandmother used to call “lording it over”

someone.

When the

goal is gratification instead of service, this still isn’t really a good deed.

There are

people, however, for whom the goodness of the act is itself its own purpose,

where action and intention are in complete convergence. They do what they

should do, because it fulfills their very nature, and is for the benefit of all

of Nature. I can recognize such people because they do not need recognition.

They are content to simply produce good and abundant fruit.

When the

deed is rightly done, nothing more is required. One gladly moves forward to the

next opportunity to be of service.

Marcus

Aurelius offers a qualification here, however, so that we do not misunderstand.

The horse will run, the dog will hunt, and the vine will produce fruit from instinct,

with no conscious reflection on those actions. They do not know what they are

doing in the same way that human beings do, and they are simply moved to do so.

Human nature, however, adds the power of reason into the mix.

I should

certainly do well for only its own sake, seeking no further reward or

gratification. Yet this does not mean that I should not be aware of what I do and

why I do it, or that others should not be aware of what I do and why I do it.

The good sought for itself does not exclude a perception of that good, as is so

fitting and necessary for all human action.

Simply

put, because I should never do good only so that it can be observed, does not

mean I and others should not observe that I am doing good. Humility is not the

same thing as ignorance, and while a man should always be humble, he should

never be ignorant.

Written in 3/2006

Stoicism and Stockdale for Memorial Day

It is perhaps appropriate on Memorial Day to offer two short talks given by Admiral James B. Stockdale, on how Stoicism related to his experiences in the military. They are well worth the read.

The Stoic Warrior's Triad:

https://www.usna.edu/Ethics/_files/documents/stoicism1.pdf

Master of My Fate:

https://www.usna.edu/Ethics/_files/documents/Stoicism2.pdf

There are also copies to read on stoicbrevairy.blogspot.com

Image: James B. Stockdale was a POW in North Vietnam, from 1965-1973

Sunday, May 27, 2018

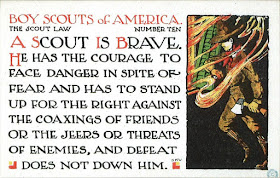

The Scout Law

As a reference for Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5.5:

These are a set of postcards from 1913, presenting the Scout Law. Though the style may seem corny to some of us these days, the content is timeless. It still works for me as a reminder of everyday virtues:

A Scout is trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous, kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5.5

You

say men cannot admire the sharpness of your wits. So be it, but there are many

other things of which you cannot say, that you are not formed for them by

Nature.

Show

those qualities, then, that are altogether in your power: sincerity, gravity,

endurance of labor, aversion to pleasure, contentment with your portion and

with few things, benevolence, frankness, no love of superfluity, freedom from

trifling magnanimity.

Do

you not see how many qualities you are immediately able to exhibit, in which

there is no excuse of natural incapacity and unfitness, and yet you still

remain voluntarily below the mark?

Or

are you compelled through being defectively furnished by Nature to murmur, and

to be stingy, and to flatter, and to find fault with your poor body, and to try

to please men, and to make great display, and to be so restless in thy mind?

No,

by the gods, but you might have been delivered from these things long ago. Only

if in truth you can be charged with being rather slow and dull of

comprehension, you must exert yourself about this also, not neglecting it nor

yet taking pleasure in your dullness.

—Marcus

Aurelius, Meditations, Book 5 (tr

Long)

I

noticed from very early on, from as soon as they decided to send me to school,

that I was never really thought of as smart, funny, charming, confident, creative,

or handsome. I also learned very quickly that these were the very qualities we

are expected to admire in others. We tend to choose our friends, our lovers,

and our colleagues by precisely those measures. We also believe we will become

successful, popular, and rich precisely because we possess such things.

In

hindsight, I maintained a remarkable sense of optimism during those years. When

I realized that emulating such characteristics wasn’t in the cards, I did my

best to work with being myself, and hoping that this could make up for the

absence of all the rest. There were a few times when it worked, but far too

many times it didn’t, and at one point the imbalance simply broke me inside.

Then, as

so many will sadly do, I started to complain, to become angry, and to feel

sorry for myself. I would put everything I had within me into an endeavor, and

I would find it completely rejected or ignored. I would become frustrated when

those who were successful, precisely because of their natural gifts, would be dismissive

of the fact that I wasn’t just like them.

My

mistake was threefold. First, I did not understand what true success even was.

Second, I did not understand what qualities were actually necessary to achieve true

success. Third, I did not understand that those qualities were hardly beyond my

power. That was why I was discontent and despondent.

Success

is not what I may receive from my efforts, but what I may give from my efforts.

Of all

the qualities I may possess, the only one necessary for true success is virtue.

Virtue

is always something I can do for myself, regardless of whatever circumstances

or gifts I may or may not have.

Let’s

say I’m not terribly clever, or outgoing, or good-looking. I can gladly accept

what I may have, and work to improve it to the best that it can be. Is my mind

slow? Am I socially awkward? Do I look hideous to others? There are certainly

things I can do to make those things better, in however small a way.

The

danger facing me is neglecting what is given entirely, or just sitting back and

feeling miserable about it.

Even

then, these qualities aren’t the essential ones, and what other people think

about them is neither here nor there. There is no need to buy any more options

or accessories. Everything life needs come standard.

Can I be

thoughtful, loving, and grateful in all of my dealings? It takes nothing

special to do these things. Put the proverbial dunce cap on my head, and I can

still do them.

I will

only choose to be ignorant, hateful, and demanding when I am dissatisfied with

who I might be, and I expect to receive whatever I feel jealous about in

others.

When I

was in the Boy Scouts, I had one of the most wonderful Scoutmasters there could

ever be. I once told him that I felt inferior, because I couldn’t always do the

things the other Scouts, who were physically stronger and emotionally more

confident, could manage to do. He gave me one of the kindest looks I’ve

seen, not one of condescension, but one of complete understanding.

“Not

everyone can do everything,” he said, “but anyone can do anything that matters.

Can you recite the Scout Law for me?”

That I

could. “A Scout is trustworthy, loyal, helpful, friendly, courteous,

kind, obedient, cheerful, thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent.”

“Can you

do those things?”

I

hesitated. “I think so?”

“No, can

you do them? Yes or no?”

“Yes.”

“Will

you do them? Yes or no? I don’t care how far you can swim, or how good you are

at math, or how many matches it takes for you to light a fire.”

“Yes.”

“Then

you’re a Scout, and one of the best. The rest is just window dressing.” I still

use that phrase to this day, thanks to him.

Written in 3/2006

Saturday, May 26, 2018

Boethius, The Consolation 1.24

“When the sign of the crab scorches the

field,

fraught with the sun's most grievous

rays,

the husbandman,

who has freely entrusted his seed to

the fruitless furrow,

is cheated by the faithless harvest

goddess,

and he must turn to the oak tree's

fruit.

When the field is scarred by the bleak

north winds,

would you seek the wood's dark carpet

to gather violets?

If you enjoy the grapes,

would you seek with clutching hand

to prune the vines in spring?

It is in autumn Bacchus brings his gifts.

Thus God marks out the times,

and fits to them peculiar works.

He has set out a course of change,

and lets no confusion come.

If anything turns itself to headlong

ways,

and leaves its sure design,

there will be an ill outcome.”

—from

Book 1, Poem 6

I have

wasted so much of my time, thinking that is just about me, me, and more of me. Someone

once said to me that the secret to life was simply taking every opportunity to

get what I wanted. I needed to be strong, I was told, and to grab onto what I thought

was rightly mine. No hesitation, no doubts. To the victor go the spoils.

Let’s

call this what it really is. It’s called playing God.

Whenever

I expect the world to go my way, I am doing nothing less than that. Whenever I

force myself upon others, or assume that the ends justify the means, or cheat

and lie to have my way, I am making myself the center.

The

crucial difference is that the ideal of God, the Absolute, however we may

understand Him, is Himself a measure of perfection. I, on the other hand, am

hardly perfect. I am a creature, not the Creator. Whenever I demand that it go

my way, I am forgetting that my own way is only a part of the way of all things

joined together, ruled by one order. I am not the fullness of that order.

“I take

every opportunity to get what I want.” Well, I may wish to take every

opportunity, but does this extend to acting selfishly or thoughtlessly? And what

is it even that I should rightly want?

Nature

will follow her own course, however much I may fight or protest. Images of

farming, and of living off of the land, are lost to most of us, because most of

us in the developed world live in a completely artificial bubble. What we make

or produce no longer reflects the way of the land, or the changes of the

seasons, or the harmony of the natural world.

We

pursue our vanities, and then use the spoils of those vanities to buy

artificial products from others, tailored for our consumption. We become

lawyers, or bankers, or fancy scholars, and then expect to be magically

clothed, housed, and fed. We care little about where any of it came from, or

how it was provided, as long as it’s all perfectly convenient.

A mentor

of mine once put me in my place by telling me that I needed to try and grow my

own fruits and vegetables, and to raise my own chickens to get some decent

eggs. This could be as much about building character as it was about putting

food on the table. He also suggested hunting for small game, but immediately

added that this might be too much for my spoiled character. Goats, let alone

cattle, he said, were way beyond my ability for the moment.

I was

deeply offended, though he was completely right. Nature will give me what I may

need, but only if I understand how, where, and when to find it and make good

use of it.

I should

not want to be served by Nature, but to find my way to rightly follow Nature. There

will be an ill outcome as soon as I think otherwise. Everything has its own

time and place.

What is

true of the harvest, is also true of the moral life. Summer won’t be spring,

and winter won’t be fall, based upon my whims. How things will happen is how

they are meant to be. How I humbly relate myself to what happens is who I am

meant to be.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5.3

Judge

every word and deed that are according to Nature to be fit for you; and do not be

diverted by the blame which follows from any people, nor by their words, but if

a thing is good to be done or said, do not consider it unworthy of you.

For

those persons have their peculiar leading principle and follow their peculiar

movement. Do not regard these things, but go straight on, following your own

nature and the common Nature; and the way of both is one.

—Marcus

Aurelius, Meditations, Book 5 (tr

Long)

What

will people think, and what will people say? It is one of those odd habits of

human behavior to take the very thing that defines us, our own thinking and

action, and then immediately allow that to be ruled by the thinking and actions

of others.

It is

something like reducing life to a game of Simon Says, or like a reflection of

the never-ending cycle of new fashions in clothing, music, or politics. Look

around at everyone else, and follow suit.

The

Stoic will never tell you not to listen to others, or not to seek wisdom and

guidance, or not to look to a good example, but he will insist that you do your

own thinking and choosing for yourself. We are all tasked with finding our own

place and playing our own part in the order of Nature, not to find another’s

place or play another’s part.

If I

can, with a conscience that is both humble and confident, know what must be

done to live well, then that is what I should do. I should not be looking at

what happens to be popular, what will bring me anything external, and what will

simply improve my circumstances.

Am I

seeking virtue above all else? That will do. Starting with a sincere effort to

practice the Cardinal Virtues, in the most ordinary and everyday of situations,

is as good a place as any. That is what will improve my nature, and therefore be

in harmony with Nature as a whole.

We often

struggle with what we think is a false opposition between ourselves and other

things. We assume there must be the presence of conflict, that my way and your

way will necessarily disagree, or that cooperation or compromise is settling

for second best.

But this

does not need to be so. I can rest assured that if I do what is right for

myself, living simply as a human being, then I will never need to do any harm

to anyone or anything else.

My own

true benefit is always within the benefit of my neighbor, because he is a

social animal like myself. My own true benefit is always within the benefit of

the entire Universe, because I am a small but integral part of it. They are

always one and the same, even when I refuse to see it. Their ways will always

converge, even when it is not immediately apparent.

People

may pursue values and goals we discern as contrary to Nature, but even such a

use of choice by others, however it may frustrate or sadden us, also serves

Nature. If nothing else, I may use it to commit myself to what is good all the

more.

Written in 3/2006

Image: Paul Signac, In the Time of Harmony (c. 1895)

Friday, May 25, 2018

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 5.2

How

easy it is to repel and to wipe away every impression that is troublesome or

unsuitable, and immediately to be in all tranquility.

—Marcus

Aurelius, Meditations, Book 5 (tr

Long)

I often

become stubborn when someone tells me that something important is really quite

easy, especially when I have found the exact same thing to be extremely

difficult in my own efforts. Dwelling upon anger will never lead to good

things.

“Perhaps

it is easy for you, since you are so much better. But for the rest

of us peasants, it’s no walk in the park!”

As

always, it is my own ignorance that is getting in the way, my unwillingness to

think the problem through clearly. It doesn’t matter at all, for my purposes,

what motive someone else may have had in mind when he told it was easy. He may

indeed have been bragging about himself, or as I suspect is the case for Marcus

Aurelius, he may well have been trying to be helpful.

Troublesome

impressions, whether they are immediate feelings, haunting memories of the

past, or worries about the future, are, in and of themselves, completely

powerless over my ability to judge them. They are simply something given,

feelings made present to my awareness. They only achieve any power when I offer

them value in my estimations, and when I allow them to influence my sense of

true and false, good and bad. Then they affect my actions.

A child

may fear the impression of a monster under the bed, a young man may fear the

impression of being unloved, and an old man may fear the impression of failure.

If he only chooses to remove these objects from his attention, because he fully

understands that none of them are important for his living, they will no longer

trouble him.

I am not

troubled, for example, by the impression of seeing people wearing bright colors

or muted colors, or of being tall or short, since those qualities have nothing

to do with their merits. They do not enter into my thinking as being relevant.

It is therefore easy to disregard them.

Now why

does it still seem so difficult to remove other sorts of impressions? The

recollection of that betrayal? Being bullied by important folks? The temptation

of a fifth of bourbon when I feel hopeless?

It isn’t

removing the impression that’s the problem at all, as I can always look the

other way. No, the difficulty is in still wanting

to pay attention. I should never blame the feeling, but I should take

responsibility for what I do with it. I still desire it, from previous habit, because

I haven’t yet chosen to not desire it. Once the commitment is made, wiping away

the impression is indeed easy, but before the commitment is made, wiping away

the impression is nigh impossible. I still want it to be there, after all!

The

feeling isn’t the obstacle. My thinking is the obstacle. And who really

controls that? I’ve usually been attacking it from the wrong end.

Written in 3/2006

Thursday, May 24, 2018

Boethius, The Consolation 1.23

. . . “Wherefore it is your looks,

rather than the aspect of this place that disturb me. It is not the walls of

your library, decked with ivory and glass, that I need, but rather the resting place

in your heart, wherein I have not stored books, but I have of old put that

which gives value to books, a store of thoughts from books of mine.

“As to your services to the common

good, you have spoken truly, though but scantily, if you consider your manifold

exertions. Of all that you have been charged with, either truthfully or

falsely, you have but recorded what is well known.

“As for the crimes and wicked lies of

the informers, you have rightly thought fit to touch but shortly on them, for

they are better and more fruitfully made common in the mouth of the crowd that

discusses all matters.

“You have loudly and strongly upbraided

the unjust ingratitude of the Senate.

“You have grieved over the charges made

against myself, and shed tears over the insult to my fair fame.

“Your last outburst of wrath was

against Fortune, when you complained that she paid no fair rewards according to

deserts.

“Finally, you have prayed with the

passionate Muse that the same peace and order, that are seen in the heavens,

might also rule the earth.

“But you are overwhelmed by this

variety of mutinous passions: grief, rage, and gloom tear your mind asunder,

and so in this present mood stronger measures cannot yet come nigh to heal you.

“Let

us, therefore, use gentler means, and since, just as matter in the body hardens

into a swelling, so have these disquieting influences. Let these means soften

by kindly handling the unhealthy spot, until it will bear a sharper remedy.”

—from

Book 1, Prose 5

Boethius

is terribly concerned about where he is, and not who he is. He thinks he has

been exiled from something by forces beyond his control, but he has only exiled

himself from the blessings of thinking and living for himself. He is still

sitting in his own library, though under house arrest. It seems to be quite a

fancy library, at that. All those books, the ones he has so cherished, still

surround him, even as they are offering him no real comfort.

I

remember how often I faced the sort of loss and despair I thought I could never

overcome, and I thrashed about, cried, or just wanted to crawl into a hole. The

books they always told me would make my life better were right within my reach.

I didn’t reach for those books, since it is never about the printed page itself.

Writing and speech are the medium, but love and truth are the message; no

amount of writings could help me if I was not willing to open up my heart and

mind.

Lady

Philosophy asks me, as she asks Boethius, to look over all the complaints that

have been made. Notice how everything of concern to us is about what happens to

us, about all the things outside of us. We point to the accusers, to the

informers, to those in the Senate, or in any body that has power, those people

we feel have been so bold as to have their way with us. We blame bad luck, and

then we go so far as to ask God to change it all, to make it all right, which

implies that He was getting it all wrong before.

The

books of wisdom, all the great texts of philosophy, won’t help, because the

attitude we even began with is all wrong. There is that moment when I recognize

that what I assumed was my worthlessness was nothing more than the most brazen

arrogance. Why am I assuming the world owes me justice, when justice for me can

only come from what I give of myself?

This is

why Lady Philosophy must begin very gently, and very slowly, in offering her

remedies. I have allowed my passions to overcome my reason. I am hurt, and I am

angry, and so I am no longer thinking about what is true and good. I am letting

my feelings toss me around, between fear and hope, or surrender and resistance.

A member

of a Twelve Step program I help run came to me recently, completely despondent.

He had been working his recovery for almost two years, but had still not found

any employment to help him make ends meet. Another member decided to take it

out on him, and told him that his inability to find a job was due to his inner

weakness. The fellow was deeply worried that he would slip, or even relapse,

because of those words.

I

understood completely. The other member, pardon my French, was being an ass. He

was venting his own frustrations at someone who didn’t deserve it. Yet at the

same time, I suggested that allowing the behavior of others to rule us was the

very reason we were helpless in the face of this or that circumstance of our

lives.

Let the

other man be an ass, I suggested, and help him with your own kindness if you

can, or pray for him if that is right for you. But don’t allow you own efforts

to make yourself better be in any way hampered by the attempts of others to

make you worse. This is a chance to improve, not to be trodden down.

As I

said those words, I realized that this advice was just as much for me as it was

for him. I should worry about my own unhealthy spots, not those of the people

around me. The world isn’t my problem. I am my problem.

Written in 7/2015